The blueprint for the refurbishment and extension of the museum is ready: over 150,000 m3 of monumental building have been entrusted to paper in flat and folded form. Sixteen boxes with forty archive boxes contain 150 drawings and approximately 100 structural detailing, along with 16 lever arch files that contain specifications (documents that specify exactly what and where materials will be used). Waiting in our corridor, they will shortly be sent to Brussels, where they will be used for the European tendering procedure to select the contractor that will carry out the project’s second phase, the actual refurbishment and extension works.

The 19th-century building is large, or perhaps better said: voluminous. Yet, one does not get the full sense of its scale when viewing the drawings. The historic building’s clear floor plans are symmetrical again and easy to read, and the old walls are between 60 and 80 cm thick which optically reduces the size of the building as drawn by half. Regardless of how well you know the building, the scale is deceptive and it is always the figures that remind you of the building’s actual size. The footprint is almost 10,000 m2, museum gallery space will total 7,400 m2 following the refurbishment and over 3,300 m2 of existing roof will be renovated, for example. Other figures are even more remarkable. For example, 15,000 m2 of thermal insulation is required for the channels and the construction’s rolled box beams will account for no less than 835,000 kg of steel.

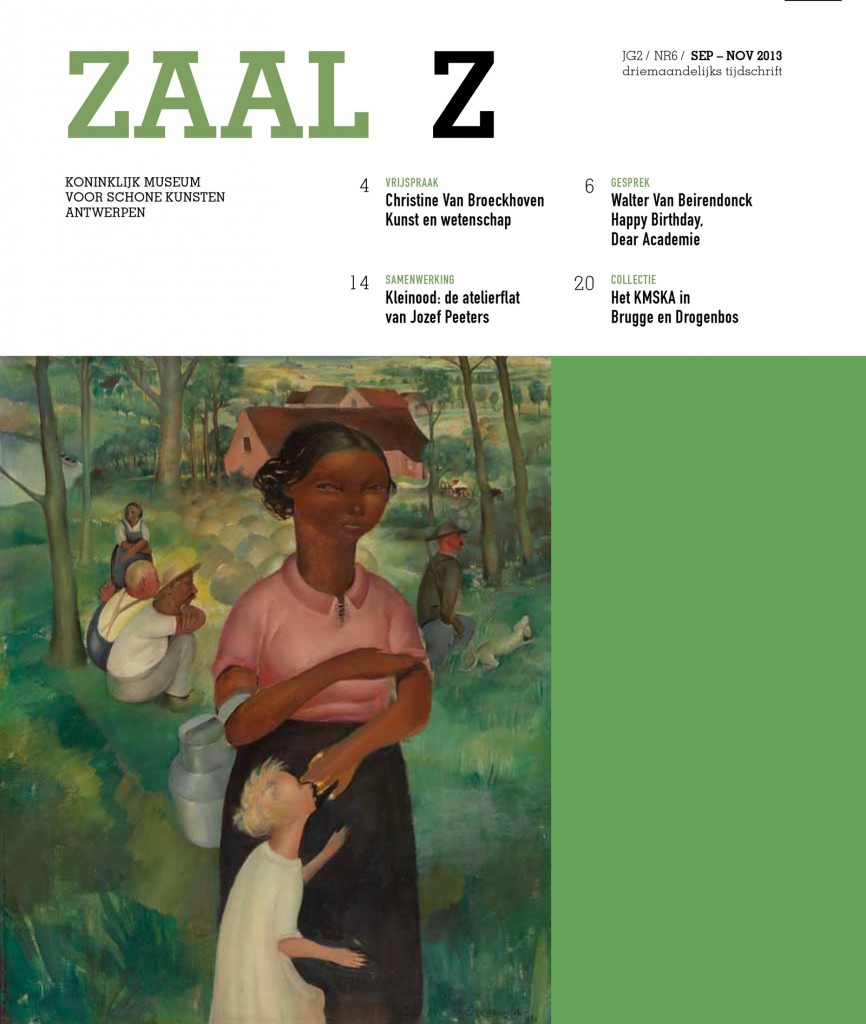

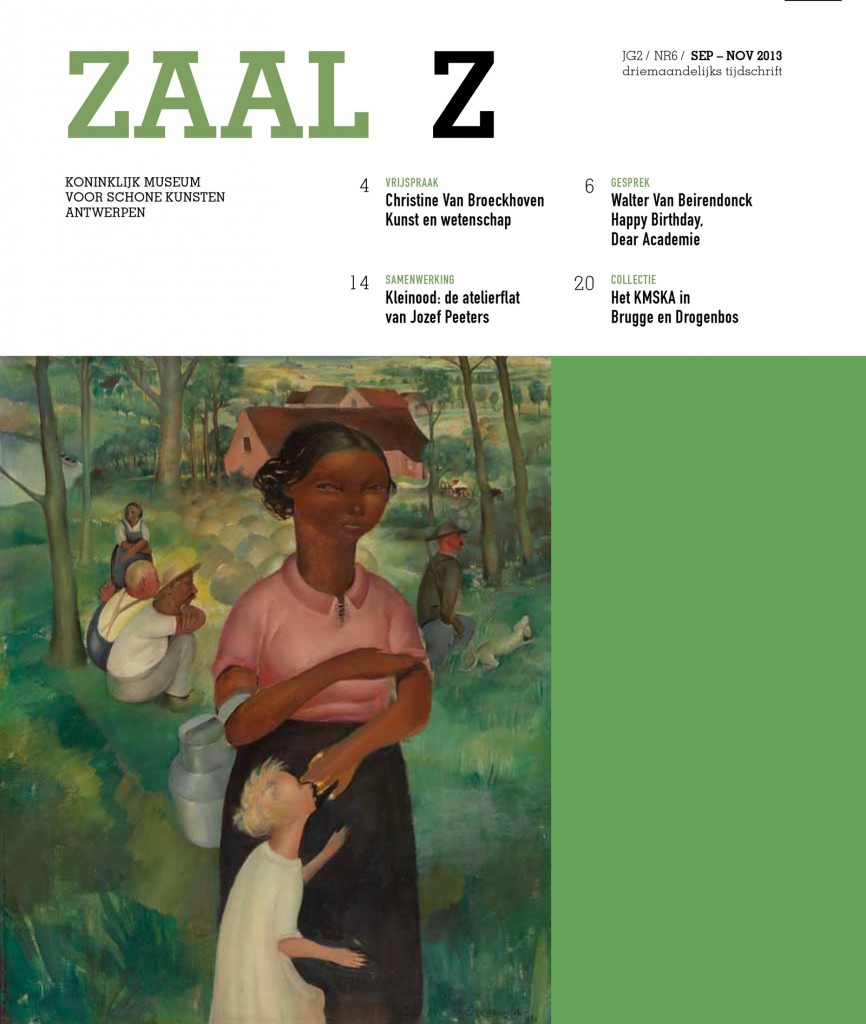

Even so, the grand lady still stands tall beyond her stature for she was designed and built to impress. She was first showcased in 1894 during the second World’s Fair in Antwerp. Aquariums for subtropical fish were immured in the ground-floor corridors for the event. The map of the World’s Fair indicated the Musée des Beaux-Arts as attraction number 118 and the sous‑sol aquarium as attraction number 119. This was the 19th century. People were fascinated by technology, travel and discoveries. It was the century in which chemistry became a science and the principles of biology were established. It was also the century in which, for the first time, large collections of art were put on permanent display for ordinary citizens. Antwerp’s Royal Museum of Fine Arts is therefore more than a museum building. It is a building characteristic of its era and is therefore an important part of its own collection.

You can download the PDF version via the link down here and you’ll find Dikkie Scipio’s article from page 40.