‘Who is the boss?’ – a column by Dikkie Scipio

Dikkie Scipio continues her quarterly columns for 'de Architect' magazine. Read the full essay below, focusing on the relationship between the architect and the client.

available in Dutch here

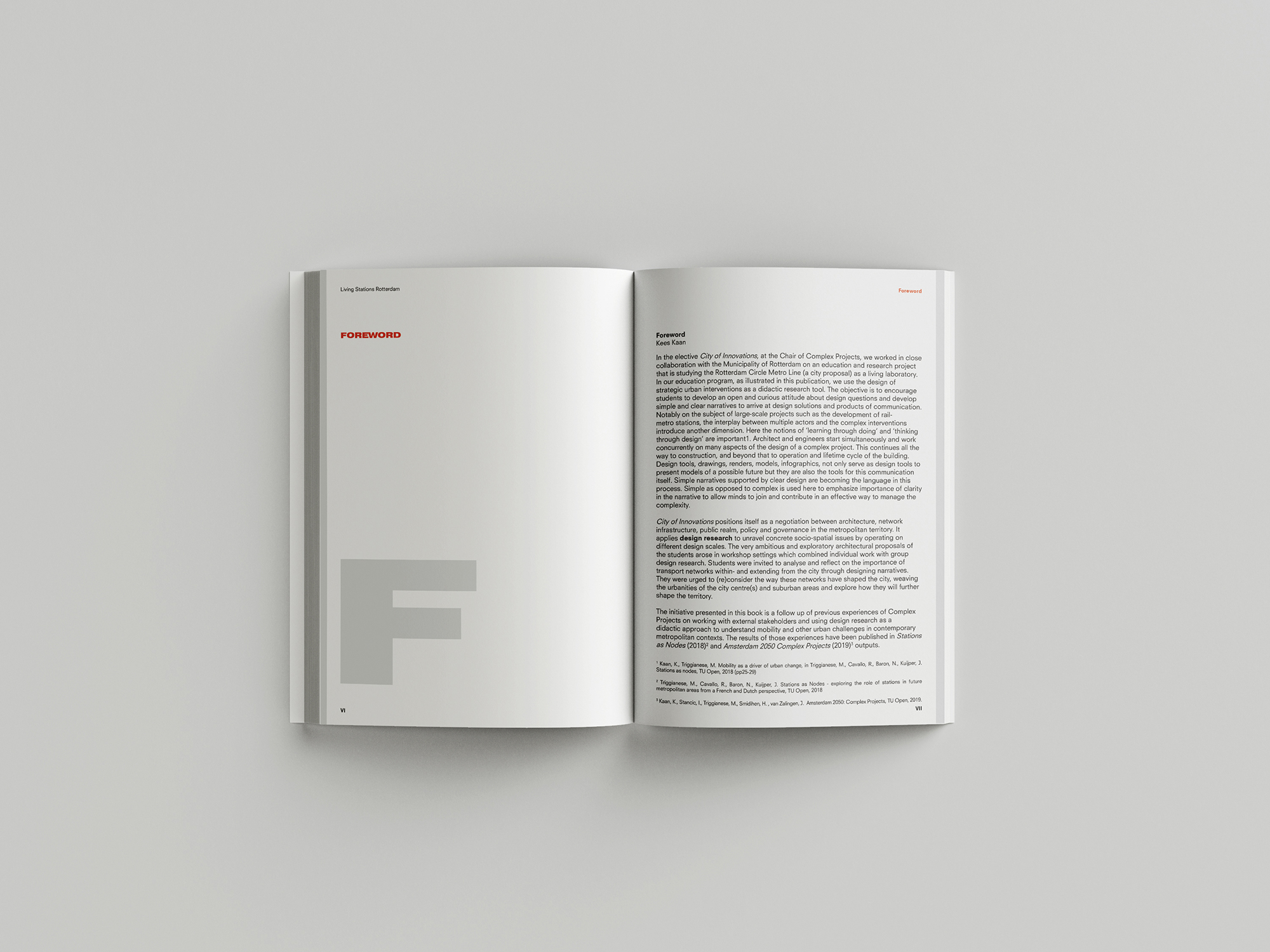

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens (1869 – 1944) was a British architect who built an impressive oeuvre of country houses, urban villas, public buildings and WWI memorials. One of his projects was a Neo-Classical villa (1908) for John Thomas Hemingway. A well-known anecdote is that during a site-visit with the client, Lutyens tells Hemingway that he wants to create a monumental black marble staircase. Hemingway replies that he doesn’t want a black marble staircase but an oak staircase, to which Lutyens responds: “What a pity”. At completion Hemingway beholds the monumental staircase and says with surprise: “I told you I didn’t want a black marble staircase”. And Lutyens apparently responded: “I know, and I said, ‘What a pity’, didn’t I?”.

As architects we hand these stories down with a sense of nostalgia. Those who have stood so firmly in their fight for quality, we feel, deserve their Starchitect status. We can now hardly fathom a world in which we could get away with such stubbornness. These are stories from a different era, long before the time of bulging-binder contracts, insurance claims, and lawyers. But even more so, these are stories from a time when the architect’s standing as a master builder and primary advisor to the client justified such eccentricities.

Today architects are selected primarily on the basis of compliance to detailed briefs outlining the technical, functional and spatial programme. A job is now so specified that it is immediately clear whether the client expects the architect to execute the programme as communicated, almost identically to the model in the brief, or whether the client seeks a ‘kindred spirit’ who will confirm the ideas presented and develop them further. While in Lutyens’ time architects were called upon for their experience, spatial and technical creativity, and ability to come up with an unexpected design that could surprise, amaze, and challenge, nowadays these aspects might lead to legal complications. It’s no wonder that only the most experienced firms know how to deal with this.

If we were to graft another Lutyens quote – “There will never be great architects or great architecture without great patrons” – onto our own times, then we see that our current reality is entirely different. Clients are very rarely a person. Most often they are complex organisations of investors, developers and users, represented by consultants and project managers, each with diverse political, economic and strategic interests. They do still exist, these independent individual clients with a vision and the means, land, and potential to realise a project in full freedom with an architect of their choice – but they are scarce. And I doubt whether these individuals today would accept a surprise like Lutyens’ staircase.

Perhaps it’s time to broaden the definition of who or what exactly a client is. Because: for whom do we actually build? As citizens, is it not ultimately for ourselves? Do we not have a duty as architects to build beyond the brief, or the programme as expressed legally. Just consider the quality of our public space, the quality of buildings that will be around longer than an expired depreciation period, the quality of our landscape. Or how about the benefits of developing of a long-term vision for housing and the environment we live in, or of new typologies and strategies to respond to social shifts?

There is a choice. Our profession is accustomed to having to be persuasive. Delivering more quality than requested does not require any permission or confirmation. We can continue to do this independently of our contractual obligations to the client. Even without them explicitly asking for it, without it costing them more in terms of investment and time, we are bound by our professional honour to add extra levels of quality. If great architecture can only be achieved by great patronage, then it is we as architects, urban planners and landscape architects who must step up and fulfil this role that has historically been allocated to patrons.

If it can be only one of Lutyens’ quotes that has stood the test of time, then I would choose this:

“I don’t build in order to have clients, I have clients in order to build .”

Prof. Dikkie Scipio

for De Architect

2nd quarter 2021

Translated from Dutch by Dianna Beaufort (Words On The Run)

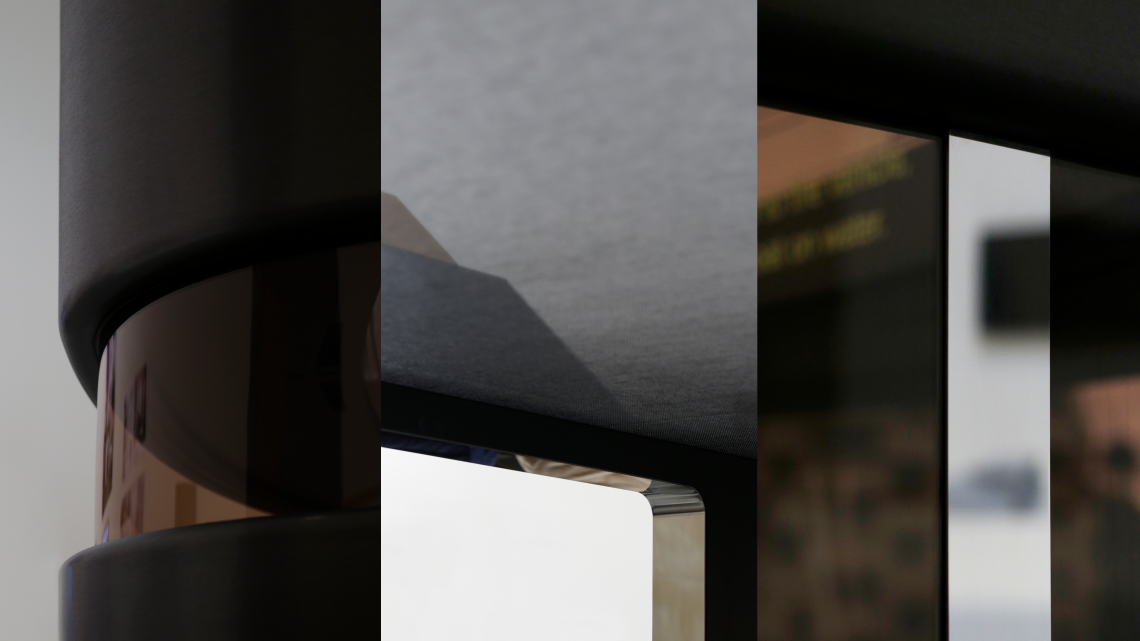

Featured above: Hall of the Heathcote Villa in Ilkley by Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens