“Sculptures in Public Spaces” by Dikkie Scipio

We take it for granted in Rotterdam, walking around in a city that is one of the greatest sculpture gardens in the world. How amazing it is to be able to stumble upon, lean against or sit on art – sometimes by world-famous artists – that gives our public space more meaning. How amazing it is to have the privilege to welcome or the right to object to the placement of new artworks – works that some cities can only dream of. We seem almost unaware of it.

Siebe Thissen is now providing us with a compendium, an excellent overview placing the art in its social and historical context, and allowing us to see the full wealth of art in Rotterdam’s public spaces. Leafing through this book fills me with pride. I see it as the ‘grand finale’ of an era, now that our ideas on public space are changing rapidly.

While public space used to be defined as space that wasn’t privately owned and was delineated by building facades and entrances, and where on occasion the space might have been entrusted to artists when conceded by the generosity of a builder/owner, today the line between public and private is slowly blurring. A new generation has emerged that no longer aims for possession, not on account of political ideals but because they do not see the point of ownership. It’s the backpack generation, those who were brought to school in the morning and told that their father, neighbour or grandad’s third wife would pick them up after school. It’s the generation that grew up with prosperity and the certainty of everything always being available, though not always from a single source or through ownership. It’s the generation that sees sharing as natural and is not impressed by ownership. The line between public and private is disappearing. The emergence and popularity of Uber, Airbnb and Green Wheels are the consequences. Even Porsche currently has a sharing programme!

So all this also has a significant effect on perceptions regarding the idea of public space. When the concept of ownership no longer clearly distinguishes the separation of public and private spaces, where exactly does public space begin and end? Or does it even end? The establishment of the first POPS, Privately Owned Public Spaces, are indeed already a reality. Insofar as I know, no artworks have yet been installed in these new public spaces that have shown any kind of different response to the space, but it is inevitable that there will be one.

Another exponent of this new sharing is the sharing of knowledge. Information used to be under private custody and traded, but now we are used to a networking and knowledge-sharing society in which it seems that having access to information is free. What we have overlooked, however, is that this is intellectual knowledge, not the know-how and experience that one physically builds by doing. It is the doing that is necessary to master a craft.

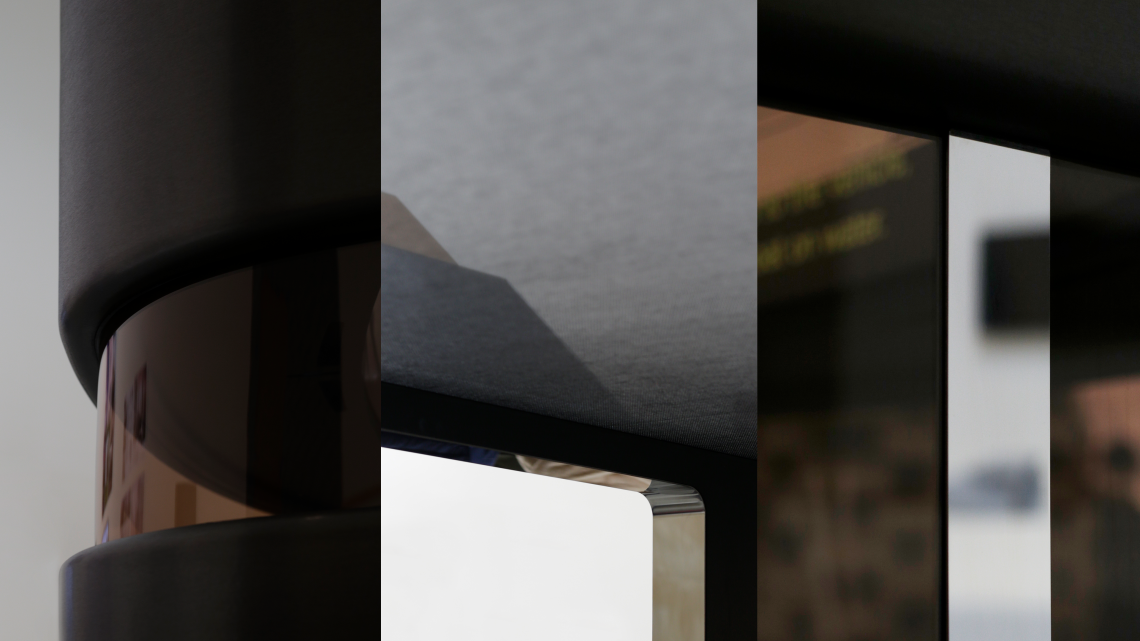

Now one of the things that make art in public spaces so special is how well they are made. They have to be, because whether they are free-standing or part of a building, they must have a suitable physiognomy and the right feel, as well as being robust enough to withstand the affections of the public and our climate. Also, the sculptures are often of such a scale that if they were not suitably constructed, they might topple or collapse under their own weight. Creating these works demands therefore not only outstanding artistry, but also a high level of technical craftsmanship. Much can be said about the meaning of the artworks, yet the skill with which these works have been made has long been taken for granted.

Just how unjust this is, becomes apparent when we recognise the serious shortage of real, skilled specialists. True tradesmen are few and far between; there are few craftsmen today who have managed to master, for example, glassblowing, the working and casting of metals, leatherworking, the many forms and applications of stonework, brickwork and concrete, and fabric, lace and pattern production. The list of ‘endangered’ trades seems infinite.

It’s a serious situation because to excel at a particular skill may require many years, even decades, of practice and patience. The urgency is clear from the fact that several multinationals have instigated programmes to recruit real craftsmen. Often older people and sometimes even the very elderly are being hired so as not to lose the knowledge once acquired and to share their expertise with younger people who can learn and pass on the value of the skill – skills that are often necessary to make excellent art.

I am grateful that Siebe’s book has lots of photographs of artists at work. It illustrates the importance of craftsmanship. It has often been artists, in fact, that have ensured that knowledge has not been lost. Let’s take serious note of this, for without craftsmanship there is no art in public spaces.

The timing of this book couldn’t be better. It contributes to awareness of the quality we should be surrounding ourselves with and, moreover, hopefully inspires a respect for the expertise necessary to achieve this. It also reveals to us our attitudes to public space, where the visual arts show us it is truly the discipline that opens our eyes to all the different ways of looking at the world – the ultimate public space. The world is changing at a rapid pace and we are here to experience it. How exciting is that?