08/10 2021

A building that sets a new standard – how we built the biggest Courthouse in the Netherlands

In 'Making of KAAN', we uncover the stories behind some of our most known projects as told by the designers who worked on them. Through personal anecdotes and lessons learned, meet the team that makes KAAN Architecten. We spoke to Marco Lanna, project leader of the Amsterdam Courthouse. He tells us about the collaborative design process in DBFMO contracts, context-aware building and embedded sustainability. Read more below!

The Amsterdam Courthouse is another high-security institutional building designed and built by our office over the past 20 years. In fact, I looked it up – the Courthouse project began around the time we finished the Supreme Court in The Hague, which you also worked on.

Was there a transference of knowledge gained in the Supreme Court and applied to the Courthouse? Perhaps certain elements the two buildings had in common?

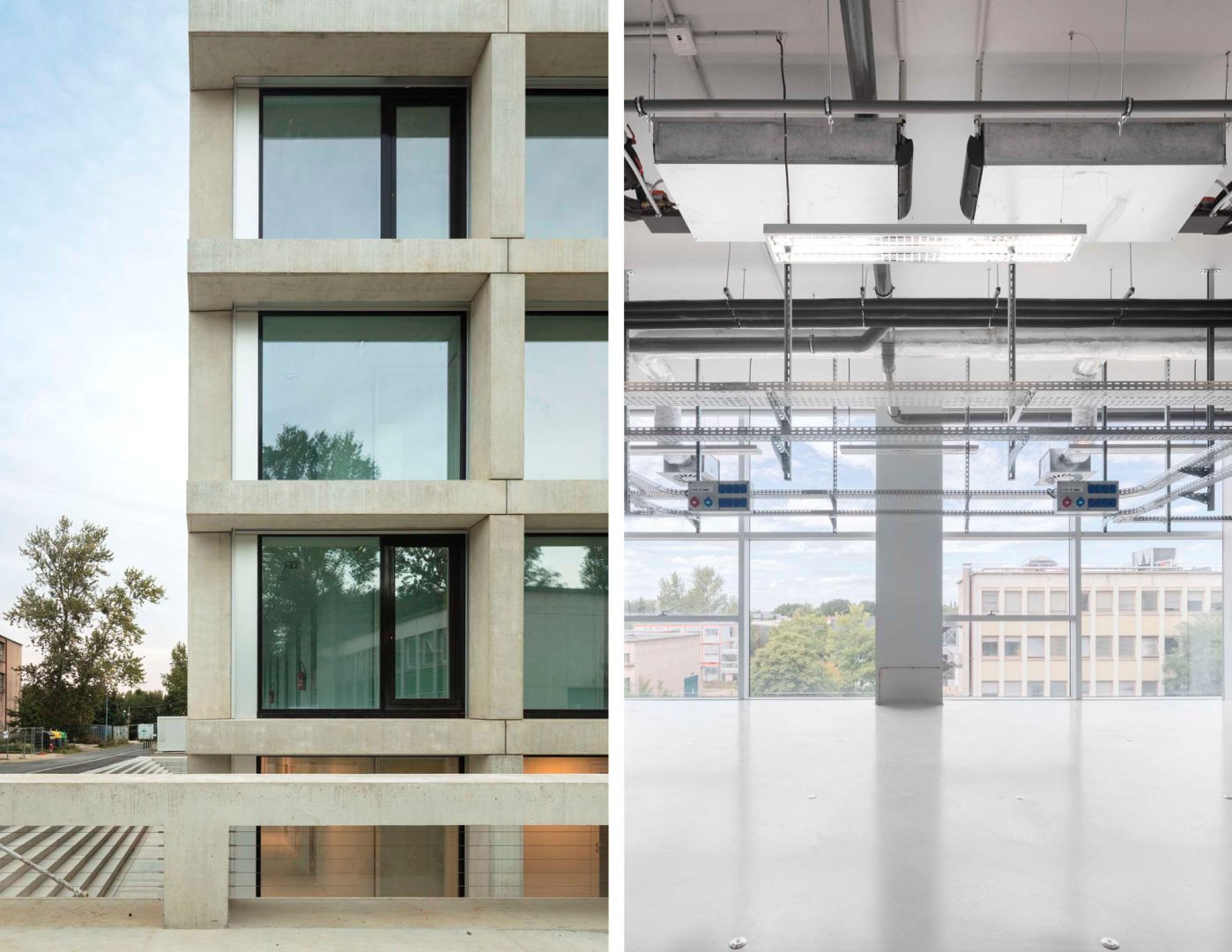

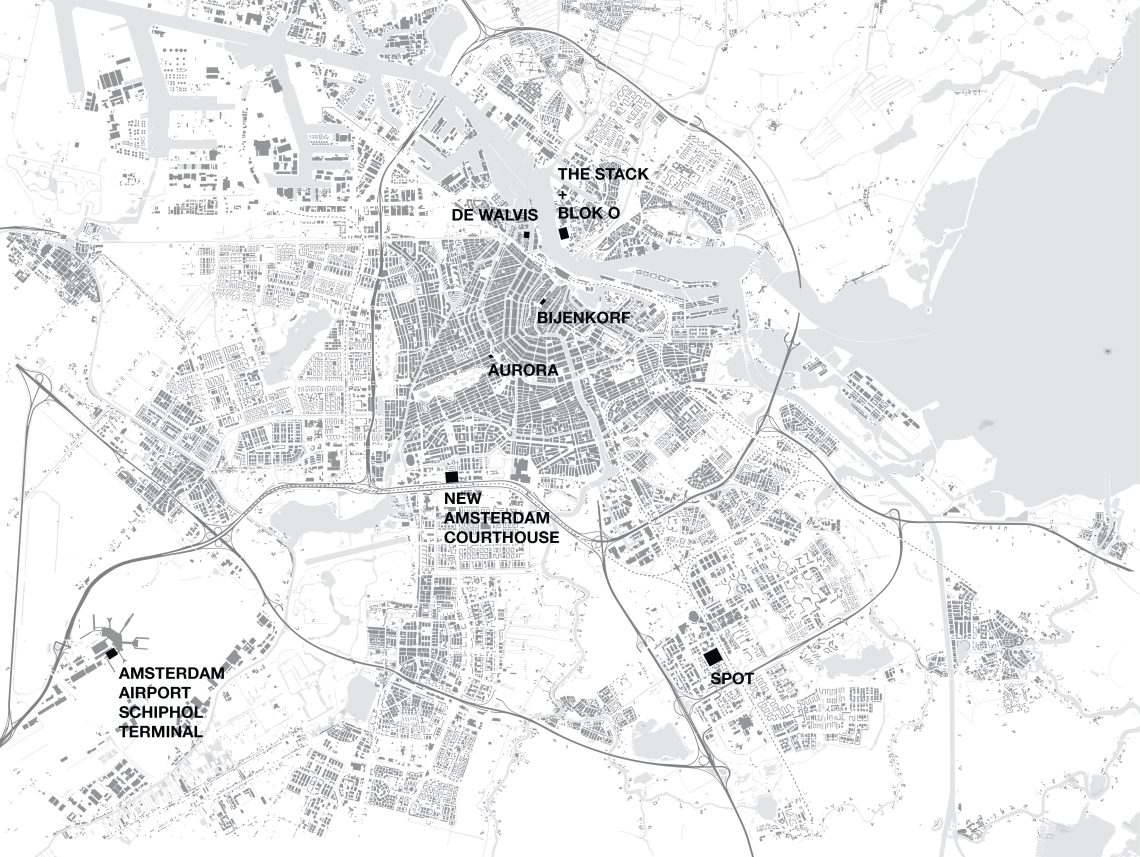

Although similar in the program, the Supreme Court in The Hague and the Amsterdam Courthouse have some differences. While the former is a tendentially closed building, only open to selected visitors under specific circumstances, Amsterdam Courthouse is a fully public institution. The urban settlement of both designs is also very different. The Supreme Court reacts to a consolidated urban structure – the historical city centre of The Hague. At the same time, the Courthouse is located in an extraordinary area of Amsterdam South, where three urban plans crucial to the city’s growth have exercised their influence. Our building reacts to this rich history and its truly public character by opening up to the surroundings.

L: Supreme Court of the Netherlands, R: Amsterdam Courthouse

Photograph by Fernando Guerra FG+SG

In French, they have an excellent name for a Courthouse: cité judiciaire. This expresses our goal for the design: a building that continues the city public space. The result is a building that serves its purpose – that of showing the process of justice, visually accessible but still authoritative, imposing in the right measure. Making room for the large public square generated pressure on the programme organisation inside and was reflected in the complex engineering of some parts. Therefore, the functional and logistical challenges of the Amsterdam Courthouse have also been much more demanding than the ones of the Supreme Court.

However, we can find many similarities between the two projects. In both, we see a very high building quality, coming from the choice of durable materials, carefully detailed and well-assembled. In fact, both buildings are conceived under a DBFMO (Design, Build, Finance, Maintain, Operate) contract. In this type of contract, the architect works in a consortium with engineers, a construction company (and its subcontractors) and a facility management party on the design from its early stages. Their expertise is conveniently reflected in the design, which results in a robust, highly qualitative building made to stay.

Indeed, we often describe the Courthouse as a future-proof building with embedded sustainability. Can you reflect on that? Did the collaborative process enable this?

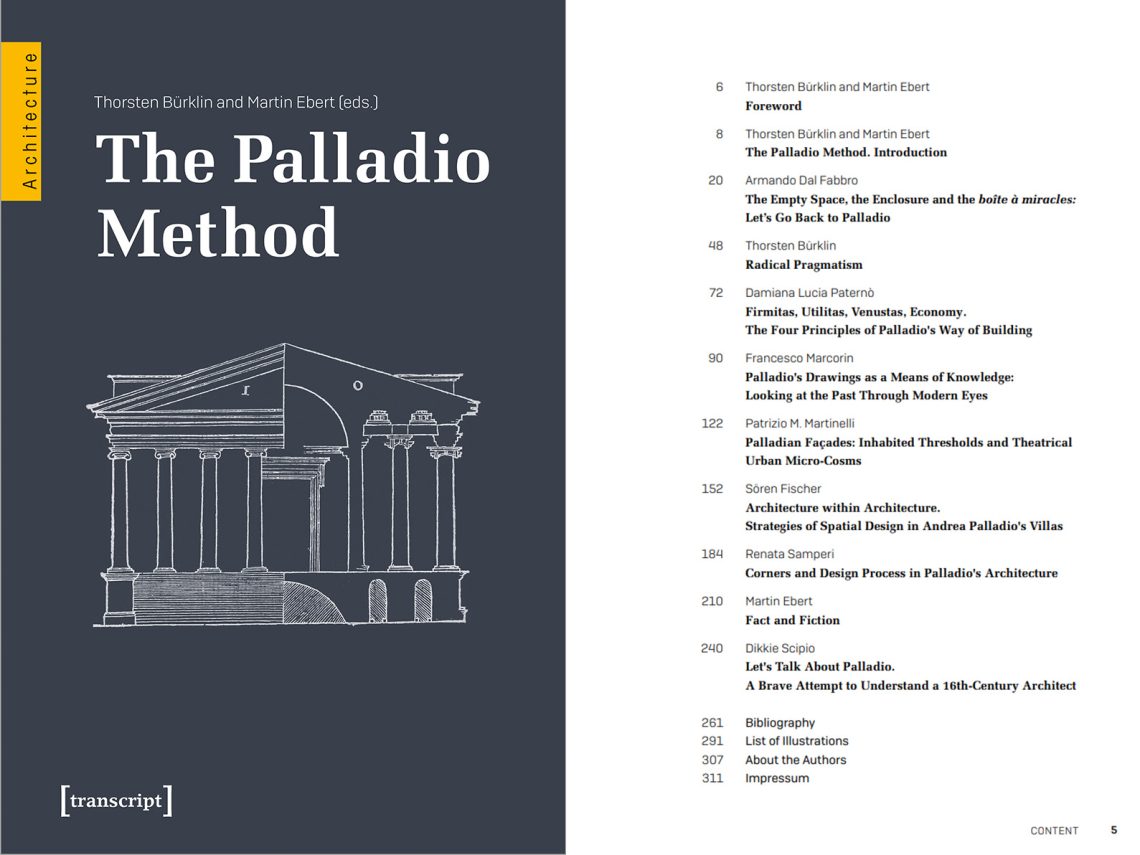

When signing a DBFMO contract, both the client and the appointed consortium enter a mutual commitment for 30 years, which involves a delicate repartition of costs in case of future transformations or adaptations. This situation forces both parties to prevent extra costs beforehand. On the client’s side, occupants and users are intensively stimulated to reflect on foreseeable changes to their primary functional process, which would require an adaptation of the spaces. Envisaged transformations are then included in the project specifications as a requirement. On the designer’s and contractor’s side, there is interest in minimising the costs for replacing or maintaining materials and installations, which would be necessary to avoid penalties.

Hence, combining both parties’ interests results in efficient and flexible layouts based on modularity for the predictable changes and additional reservations for the less foreseeable ones. In combination with state-of-the-art, technical solutions, this results in a building that needs virtually no heavy maintenance over a long time. We have learned to call that “embedded sustainability” – a concept that spans way beyond the mainstream sustainability features.

Photograph by Dominique Panhuysen

In light of this, one could reconsider some elements of the flashy greenwashed sustainability. I am highly conscious of the opportunity and responsibility that the building industry is taking up by broadcasting a “green” future. Our world needs a change and whatever moves in that direction is good. However, a lot of this greenwash is still too experimental or fragile. Take wood as an example: it needs more treatments and is subject to replacement much, much earlier than natural stone. Greenwash is a trend that very much tunes on the needs of today, but a courthouse should be timeless and designed in a way that preserves its image unchanged over time.

Suppose we analyse the energy demand throughout a building’s lifespan, including its construction, transformations, demolition or dismantling. In that case, we see that most energy demand is in the first and the last phase, where the transportation of materials, disposal of debris and the use of building facilities require energy. So the best way of thinking of an energy-neutral building is to make one that lasts as long as it can. This is not just a matter of engineering. For a building to last long, it must gain social recognition and relevance in the community of its users.

Photograph by Sebastian van Damme

This is precisely what happened with the amazing sculpture Love and Generosity by Nicole Eisenmann on the forecourt. The press coverage for it has been probably higher than the building’s itself. Lately, when I pass by the Courthouse, there is always a professional photographer shooting the sculpture. Secondly, there is a group of skaters and BMX-ers who enjoy the ramps and benches of the square. Once I talked to them for a bit, and they told me an incredible story. In the beginning, they were shooed upon their arrival. But then, someone I later learned was a Courthouse representative – visited a local skate guru who addresses the rest of the skating community. Together they established some ground rules; for example, no grease allowed on the benches to preserve the lawyers’ suits. And from that moment on, skaters were welcome again.

A genuinely public building represents the institution’s authority while opening up to the community; it involves art in creating symbols that enrich the narrative and give a sense of belonging.

The construction phase of such a building must have been quite a venture. Can you walk us through some of the challenges you faced there and how you, eventually, dealt with them?

In Italian, there’s a beautiful, old word: sprezzatura. It refers to something that looks easy and obvious but conceals a great deal of engineering. I like to think of this building as an example of it.

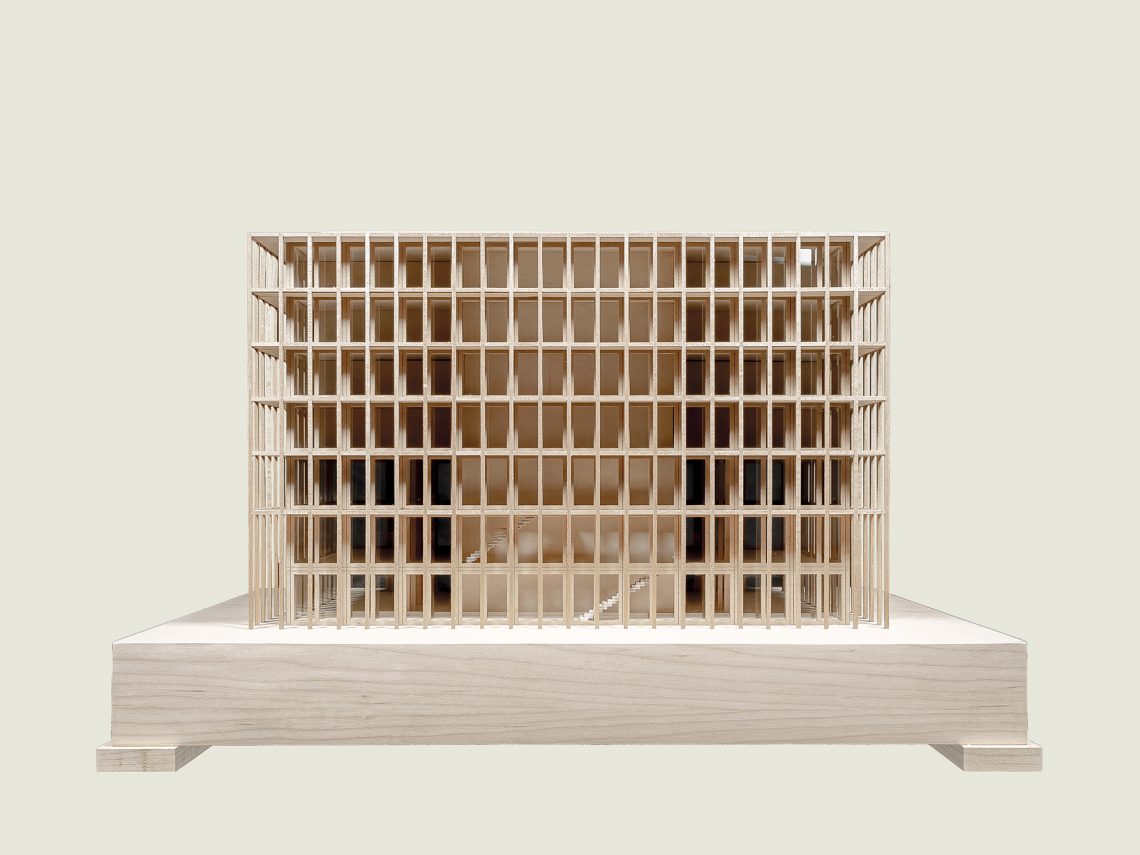

When I looked back at the design documents of the first dialogue phases, before a contractor joined our consortium, I realised that the building had the same programme organisation, massing, façade design, and type of natural stone already 6 weeks after the start of the design! We knew by intuition from the very beginning that this was the right model AND the right design. The rest of the process has been a long journey of engineering and fine-tuning. We benefited from the expertise of the engineers, the facility management company, the main contractor, and the subcontractors. The peculiar organisation of a DBFMO design process confronts the designer early on with the need for solutions to design challenges that minimise risks.

Photograph by Dominique Panhuysen

I like to mention the design of the façade as an example. We wanted the columns to be as thin as possible since the building concept is about showcasing the use behind the envelope and not making it carry its own significance, as most buildings on the Zuidas do. At the same time, the façade line in the foyers needed to be flat to prevent people from hiding behind a column which implied putting them outside the glass line – structural profiles inside the metal case, wrapped with insulation. This required consideration of all kinds of challenges early on: production and montage tolerances of the steel parts, sufficient exposure of the structural profiles to the inner temperature to prevent deformations, montage sequence and agreements on the position and size of seams, bolts, welding… These are things you usually deal with during construction. In this case, they were anticipated into the design process by putting the façade contractor, steel supplier, main contractor, structural engineer, building physics engineer, and the architect around one table. Only after two lifesize mock-ups and conceiving numerous innovative engineering methods for steel production everyone had enough confidence that the designed solutions were valid enough.

Photograph by Dominique Panhuysen

Circling back to the thread of knowledge transference – what are the main takeaways from the Courthouse for you? What do you see being embedded in our next projects?

There are multiple takeaways from this project. In my opinion, the most important one is the power of narrative in the design process. As strong and right architect’s intuition can be, there are moments in the design process where hundreds of other people operate very far from the main concept source. How do you make sure everyone moves in the same direction?

Photograph by Dominique Panhuysen

The architect’s authority is essential when exercised constructively and inclusively, as it creates a sphere of trust from which everyone benefits. But this alone isn’t sufficient. We had to respond many times to our own question: what is this building about? We like to work with presentations featuring infographics, a graphic language that can’t be misinterpreted. By constantly referring to the founding ingredients of our story, as communicated to the client and our whole team, we kept a screenplay to which new ingredients would add up in time as the original core values evolved. In the same fashion, all design choices we needed to make, even and especially when in contrast to the Program of Requirements, were documented, explaining alternatives and justifying why we considered the chosen option the best one.

Photograph by Dominique Panhuysen

There is also another important takeaway. The DBFMO design process generates the architect’s awareness of the efficacy and appropriateness of the design choices when time is an important factor. Together with experienced facility managers, you get to think early on about matters such as: how big and well connected does the furniture storage need to be if FM has to arrange the layout of a Courtroom in a contractually given time? Where to place a coffee corner considering the natural routing of people through the building so that revenues can be maximised? Or more technically: what is the best compromise to still realise that nice plaster ceiling in the foyer, considering the frequency of maintenance of the installations behind it?

Photographs by Sebastian van Damme and Fernando Guerra FG+SG

We have learned to think this through at an early stage. And the great thing is that so many people in our office had the opportunity to work on this big project – so this knowledge is now widely spread in the office. After all, once you make a building that sets a new standard, you aim at no less for your next project!

————–

Marco Lanna is one of the Managing Architects of KAAN Architecten with extensive experience in developing and managing complex building projects such as the Amsterdam Courthouse and Supreme Court of the Netherlands.

Interview by Valentina Bencic. The original text was edited for clarity and brevity.

Featured image by Dominique Panhuysen.