To start us off, can you reflect on what the past year has been like for you personally and/or professionally?

RG: I think for me personally and professionally, it’s the year that it really hit me what it means to run an office, to understand that there are families that depend on the salary they’re making in this office. And I’m talking only about our office here in São Paulo, 7 people. But it is 7 families, and it was hard.

So in the first few months, it was just about understanding which projects are going to get cancelled, which ones are going to continue, and which ones are going to be paid.

We got very lucky that the housing market exploded in Brazil. People living in small apartments realized they wanted bigger houses, better living conditions, and they want them now. Ultimately we managed to secure new projects to tide us over. And now, as we’re slowly seeing the end of this, people are making more plans for the future. The institutional, urban, cultural projects we’ve had are also starting up again, everything is coming together.

Personally, of course, it was quite difficult being home. I have two small children, ages 5 and 7, and they’ve just learned how to read and write. Actually, WE had to teach them how to read and write while keeping up with our jobs. And that was really, really tough. But of course, it does bring you together as a family, you start being a little community, and yeah, in the end, it was OK.

What about you Marylene? We’ve checked in with you in an earlier interview about how you’re handling lockdown…

MG: That interview was in May last year, so it was a different time, right? Pre-pandemic we were already quite used to working remotely with the Rotterdam office, so the most noticeable change was in the comfort level – no more being in the office space and all the comfort that comes with that.

When the lockdown happened in March, we mainly lost time adapting, negotiating, communicating. So, we asked for time to be able to succeed in the projects we were doing. And we did, with a small delay – if you consider the usual duration of projects. Turns out decisions take more time, not actions.

After that, we focused on our Parisian office, setting up a proper branch and a new space in Le Marais. It was important to go on with this project. We got the keys to the new office space in October, on the day of the second French lockdown!

Realistically, in the months after that interview in May, we saw everything (in France) stop. No tenders or competitions; projects put on hold. November and December were particularly stressful, without perspective. But now, from January I see things starting up again. And I am optimistic.

With this crisis, I can see minds changing. What we struggled to explain before, is now easier to understand – the need for accessibility, light, quality of space, robustness, steadiness, discussions of sustainability versus greening. There is a step forward, maybe not a big one, but things are slowly changing. And now that it is a more competitive market, Architecture is back on the plate. It may turn out to be a good crisis. (laughs)

DS: Wow, Marylene! I need to jump on this for sure. It’s quite interesting what you say about the quality of space, that it suddenly counts again. Because we’ve struggled before to get that point across.

We set up a research project with the office and with the university in Münster where I teach. It was a survey at first, called ‘Your home is your shelter’. We had this idea to ask people about the comfort and quality of their homes since it’s such a rare occasion they’re spending so much time enclosed. And some answers were quite obvious. People with children and families expressed their desire to have an outdoor space, a garden, a balcony…But as most participants were young students, they said they’d like to have more functionally non-determined spaces. Spaces that are more flexible and allow for transformations beyond just 4 white walls, a floor and a ceiling. And this is something very difficult to explain to a client. So hearing you say that you feel clients are more inclined to a dialogue about the quality of space is something I welcome.

Excerpt of the ‘Your home is your shelter’ survey

RG: For sure, I think it’s just a given that crisis is a huge opportunity for quality to come back, right? When the economies are booming, people want to build and they want to build fast and make a profit, there is often no time or space for quality. But when you’re in a big crisis like this, you’ve got to have something special, otherwise, you’re not going to be able to sell it. It’s pretty simple.

And what you said Dikkie is just so interesting, because what the people in your research want is not more spaces but more experiences, right? They’re lacking experiences.

And this is a word that keeps appearing in most conversations I have lately, with engineers, reporters, clients, developers, investors…This new generation is focused much more on experiences than on spaces.

DS: Yes, that was already a thing before the crisis, but now even more. I mean, their world is on their computer right now. So there is a strange disconnection between the experience of the mind, the body and space. Right?

RG: Yeah, and it’s all so much more subjective…

DS: I might be falsely optimistic here, but I really hope that this crisis and the rising demand for quality can improve the spaces we design. Not only with materials, but with sound, touch, all these different things you can experience. This is something really difficult to teach. I have to tell my students to step away from the screen and go touch the walls of their rooms, their chairs and so on… Especially now…

Speaking of, Dikkie and Marylene, you are both teaching in different architecture schools. What has that experience been like during the past year?

MG: This is my first year of teaching – ever, so my experience is probably a bit warped. I was teaching in the fall semester to the 1st year bachelor students. In September, we weren’t in lockdown so we got to have a few physical studio sessions, then later in October we switched to virtual teaching. I must say it was difficult. I’ve had students with great connection on a proper laptop, others with bad connection on their phone, on top of the mountains in the Alps, another one in Martinique, in a different time zone…(laughs) Somehow, we made it work, but in December and January we could get back for in-person studios, and… Students were just so happy to be together, and happy to see us, teachers. Because we could speak through our gestures, our pencils. It was all a bit emotional. Overall, this past year, students had to be adaptable and flexible, so I hope that is also a skill we managed to impart to them for the future.

Dikkie, how was your experience in Germany?

DS: Well, I haven’t seen my students for basically a year now. And we’ve now also heard that the next semester will be virtual too. And it has some advantages, but also a lot of disadvantages.

At this point, we’ve already gone fully digital. My students are completely immersed in this 3D world, gaming and all. So I get a lot of projects that are actually gaming environments. I discovered it when we were doing a studio about Notre Dame. The first thing we looked at was the Assassin’s Creed 3D model of the cathedral and how realistic it was. I mean, the students have modelling software in their hands already, and they can build up a whole world there. With the gaming industry getting better and better, I see more architects wanting to shift to that industry too, to create designed environments rather than just historical reproductions…

I’ve also had some bachelor students tell me they were inspired to become architects after playing Sims all day…

Funny you should mention that, cause The Sims game has initially been designed to be an architecture simulator rather than a video game…

DS: Oh no, I didn’t know that! If that’s true then I could suggest some improvements… (laughs)

MG: Indeed, this gaming environment is a part of the architecture. Some people are spending a lot of time immersed in that world. The difference is in the sensory experience of it – how do you translate the softness or the hardness of a material, how do you express gravity, the feeling of going from a confined space to an open one, the transitions… How do you translate these feelings digitally?

DS: I know! I’ve discussed this with my students too. Their point was that the gaming industry is already so advanced, there are ways of interacting with these environments through VR, holograms and other devices. So it’s coming closer and closer to the real thing. And I’m not fighting it, I embrace it as a part of the architecture. It doesn’t obliterate the real-life aspect of it.

RG: Although I don’t teach, on this matter, I can tell from my children that they really do lead this double life, immersed in their screens and online games. I had to limit their time. When the lockdown started, the first thing I did was buy 6 chickens for our garden…

DS: Really?

RG: Yes, and I said to my kids: ‘You will spend every afternoon outside with those chickens, I do not want to see you inside!’ If I let them, they’d be inside behind a screen – first in class, then for fun. That is basically their whole lifestyle. So when you speak about your students and this other life that they have, this is the same thing – with just ten years difference.

I find it fascinating how important that world is… I think we’re not the right generation to understand it, we grew up differently. Perhaps because our generation doesn’t understand it, there’s a lot of space for improvement in the way we design the buildings that we build?

It circles back to what Dikkie’s research was saying – about the need for experiences in the physical space around us, and how this demand got projected into a virtual dimension, where we’ve built a different world. We’ve even appropriated the architectural jargon – like online platform, forum, chat room

DS: Yeah, it’s very double. If we imagine, let’s say wood, we think about several different types of wood, how it’s cut, how it smells, we know how to put it together. But for those kids, wood is an abstraction, it has no connection to our mental image. It doesn’t exist. It took me a long long time until I understood that I am teaching people who think that the choice of material means clicking one of the boxes in the right corner of their drawing, that it has no relation to the real thing. And if we don’t teach them that, then that’s a loss. If we are not careful then this knowledge will be lost.

This brings me to another thing I wanted to discuss. Dikkie you’ve been vocal about quality, especially in materiality as a cornerstone of sustainability. Does that exclude more high tech solutions?

DS: No, definitely not. I don’t like to put industrial production and craftsmanship in terms of either one being good or bad, both can be made well. Quality is in how and with what intention the products are made and applied in architecture.

RG: Speaking of high tech solutions…Here in São Paulo I am on several committees for the sustainable development of cities, we meet to discuss strategies as well as business opportunities in the sustainability sector. This puts us in contact with companies that are building the actual technology, we hear and learn about carbon footprints of metropolitan regions, decontamination of rivers with phytorestoration, extraction of methane from water etc. I enjoy that they are business owners and they run their business with this kind of advanced thinking. It’s about communicating and building strategies to actually use the knowledge that we are creating. How can we push it further? Often it’s not about finding a perfect solution, but rather something the public will understand and accept, something that can be financed and applicable now.

You know, I’ve never really understood the term smart city, but I do understand a resilient city. We have to find ways of making cities sustainable for the next 80 years, 200 years…For that we need to start thinking systemically, and looking at the entirety of our processes.

DS: Yeah, we have to step back and see the bigger picture. But that’s already difficult in our tiny country, in the Netherlands. You’d be amazed to see how many questionable decisions can be made only in this small area, now imagine France or Brazil…It’s not easy to solve it.

RG: Yeah, but I don’t think it’s even about solving it as much as rectifying the warped idea of sustainability in people’s minds.

MG: But I also feel that people are learning more and more about this and dismantling the old beliefs. I remain optimistic. In Paris, big moves were made to accommodate bicycles, now I think there is more bike traffic than in Rotterdam! It’s a combination of reasons, of course – fewer people take the metro because of the pandemic, the strikes of the previous years – but when I think about Paris 20 years ago, it was a city for cars. Now it’s a different story. It’s not completely done, but it’s changing, and I welcome this.

DS: Do you think this has to do with people just switching from cars to bikes, or is it because many people are moving away from the city?

MG: It’s both, I think. But yeah, Paris is losing inhabitants, around 12 000 per year for the last 10 years or so, mostly because of the price of living. Once again, I think this crisis is a good kick. I see rent prices coming down, albeit slightly. Also since the pandemic started, the city of Paris set up requirements to be included in the local urban plans (PLU) – demands for more diversity, creating collective spaces, flexibility, refurbishments rather than demolitions, preserving existing nature, creating fresh blocks, sourcing local materials etc. These are not precise measures, but instructions. And we’re aiming at results…

RG: Right now, in Brazil, people still want to leave the city. Infrastructure could be better, everybody wants an outdoor space, a garden…It’s a social condition, it’s just the way people are. They’ve always been willing to sacrifice a certain amount of time for their commute so they can enjoy the advantages of both their home and their work area. But I also think this attitude will change for the better after the pandemic…

MG: Yeah, I really do not miss being on the train or the metro for hours, going from one meeting to another, only to have 10 minutes of productive discussions. We’ve saved that time for real work and life…

On that note, do you have any final remarks on where we’re headed?

MG: The architectural working method remains collective. Our profession is not (only) about producing excel sheets. The essence is in cracking problems through drawings, and a drawing is a collective document. To do that, it is easier to be together around one paper, one plan, because questions and doubts hardly pass through the screen.

DS: I must admit I’m intrigued by Marylene’s optimism about this. (laughs) I have been working the past year through this pandemic, but never really stopped to consider the fact that it might also bring good things. And ultimately, I must agree with you Marylene…

MG: (laughs) I do want to specify that I don’t think COVID was a good thing, eh? But that ultimately the crisis might yield good things.

DS: I’m glad that we had this talk, cause now it makes me think that I should focus more on what positive outcome we can bring to it, as architects. Let’s embrace what we can gain from it, not just what we’ve lost.

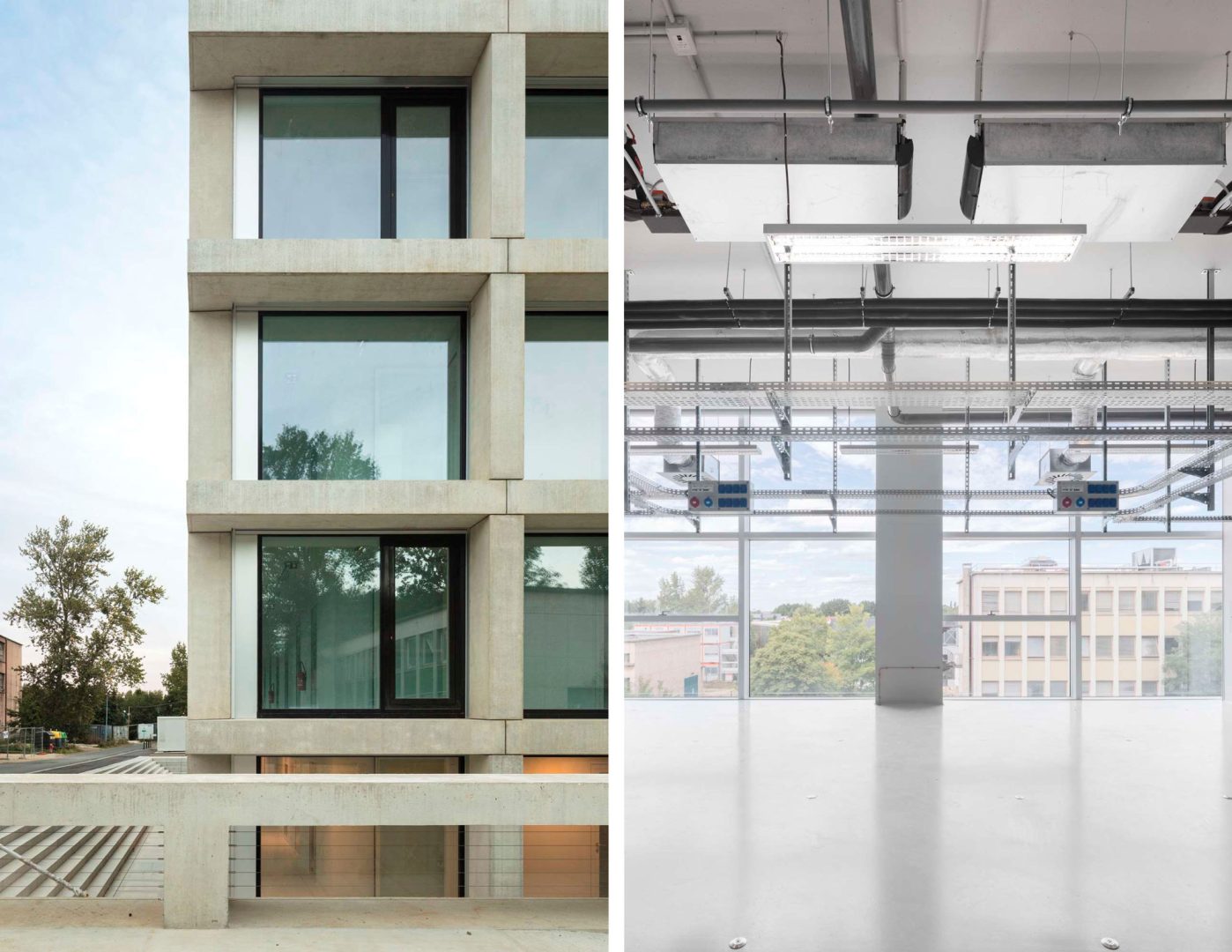

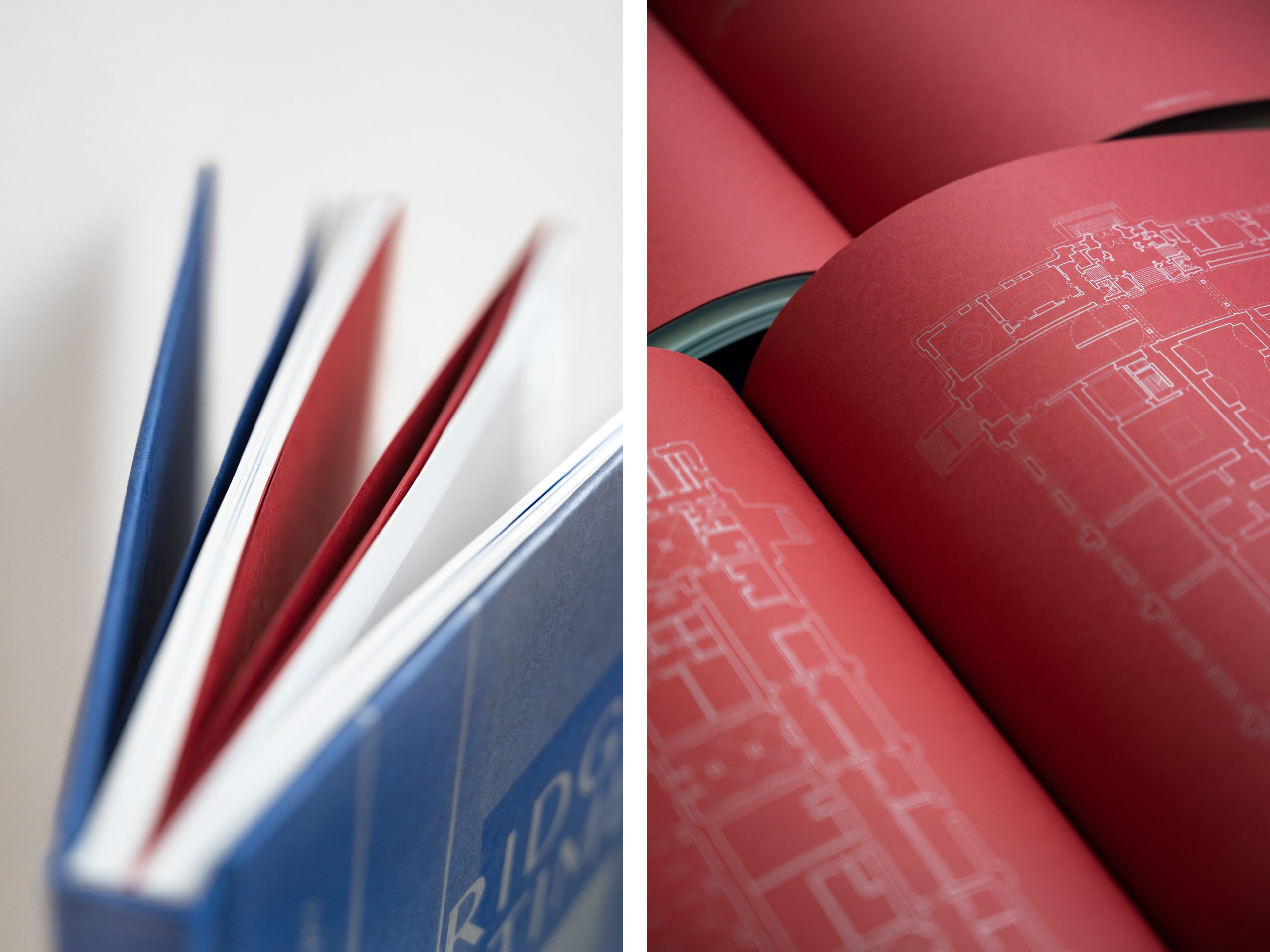

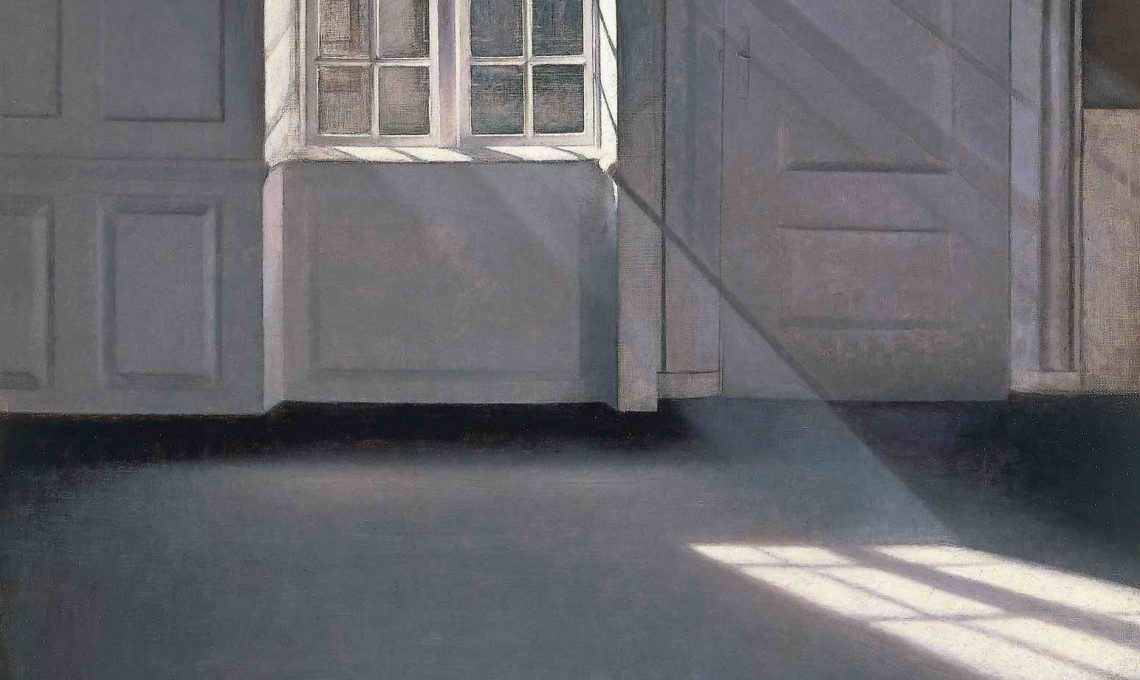

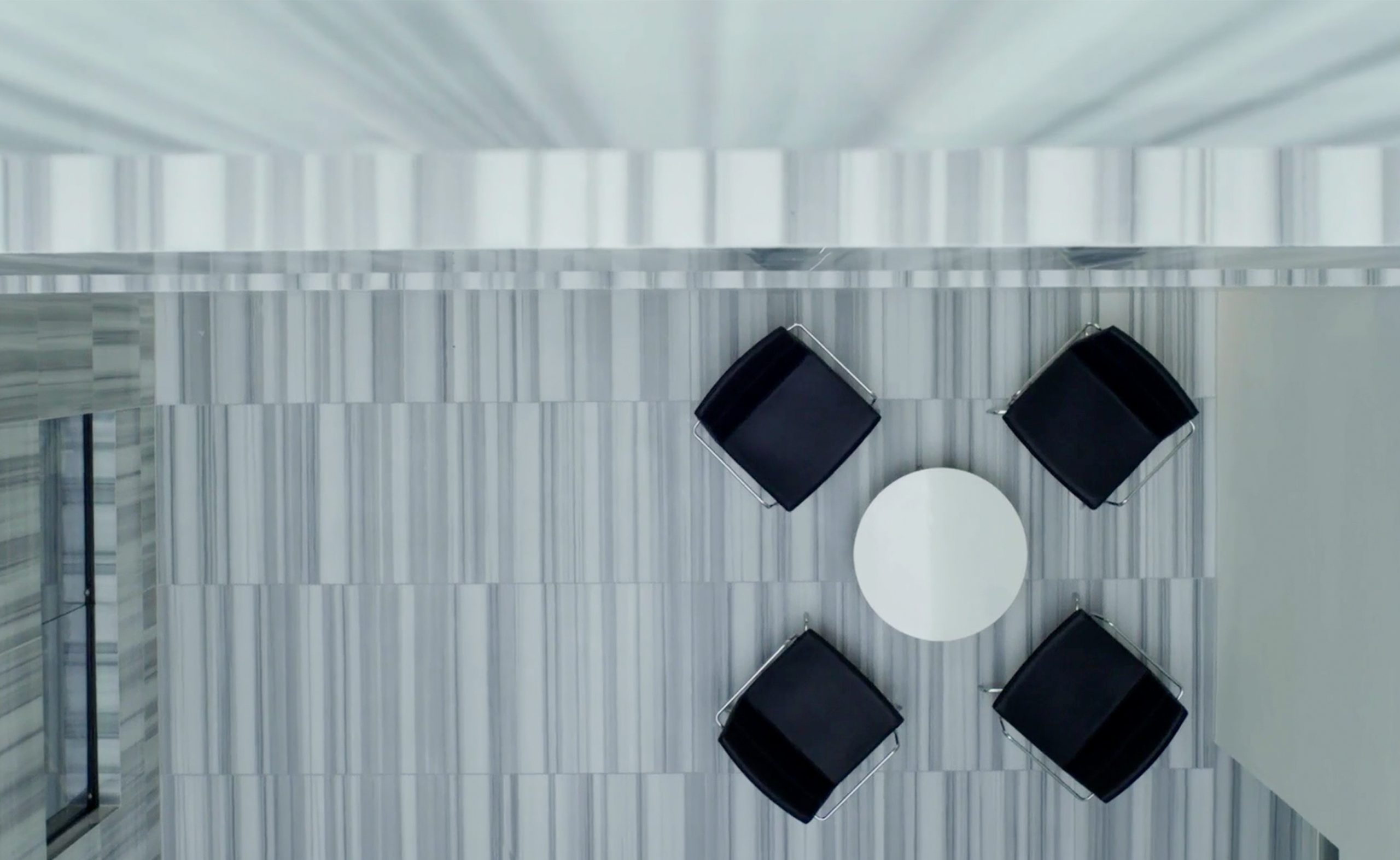

Photographs by Justina Nekrašaitė

Photographs by Justina Nekrašaitė

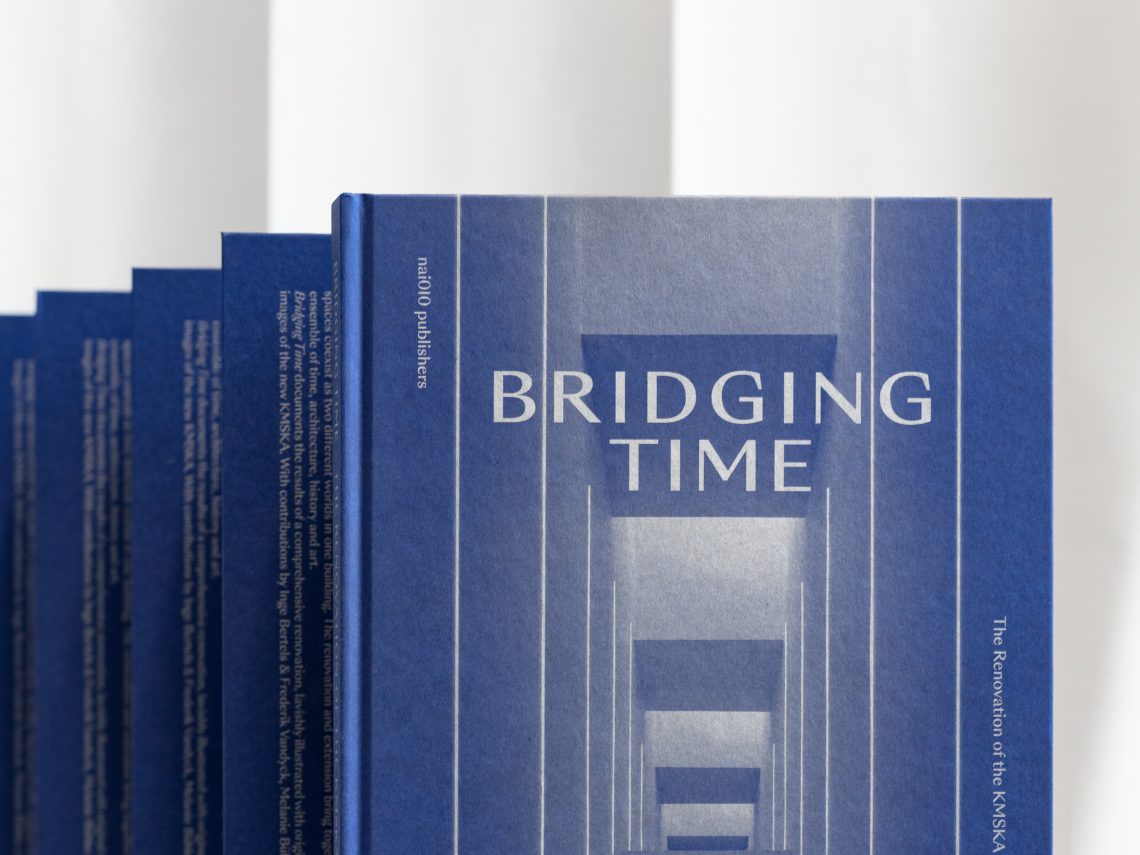

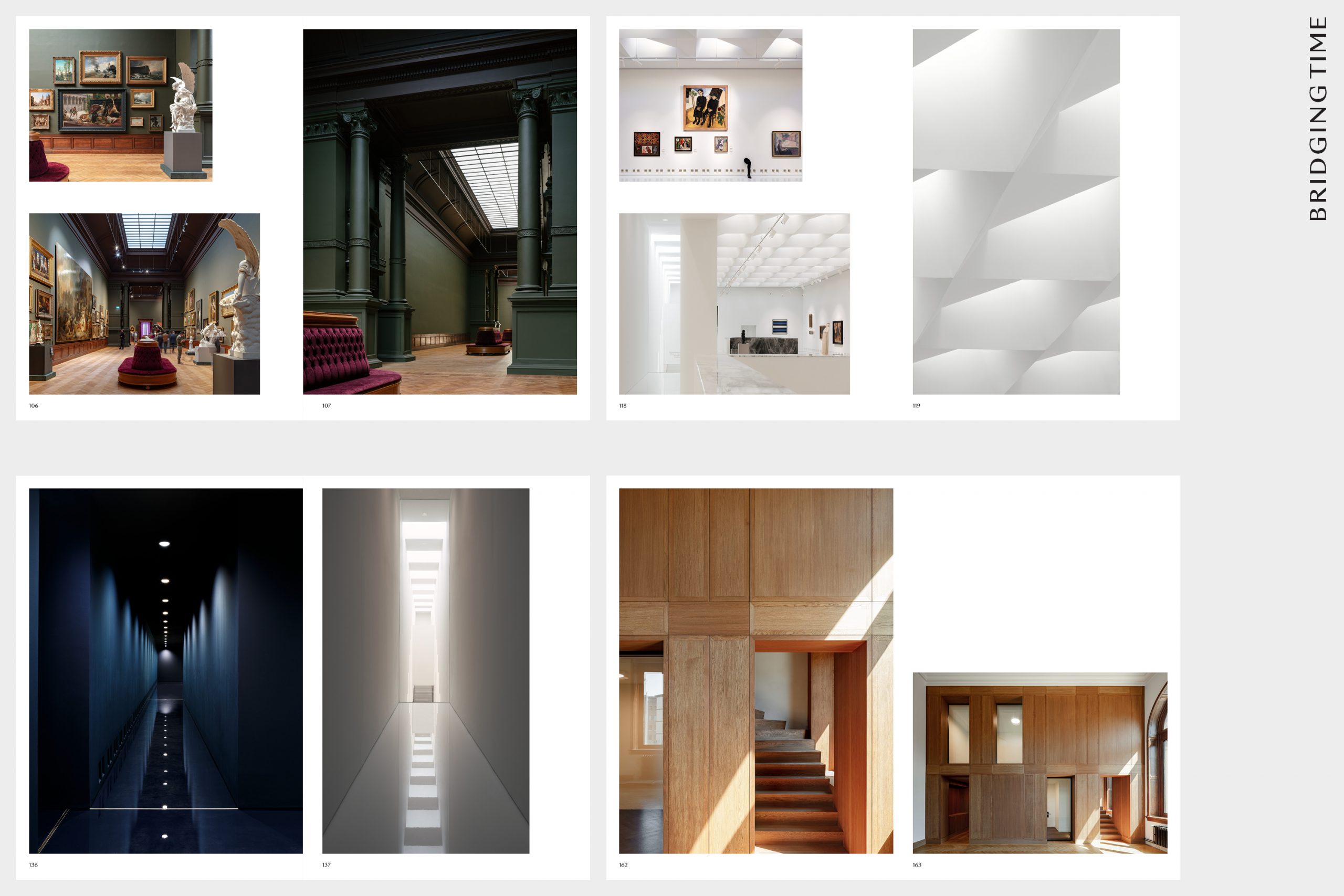

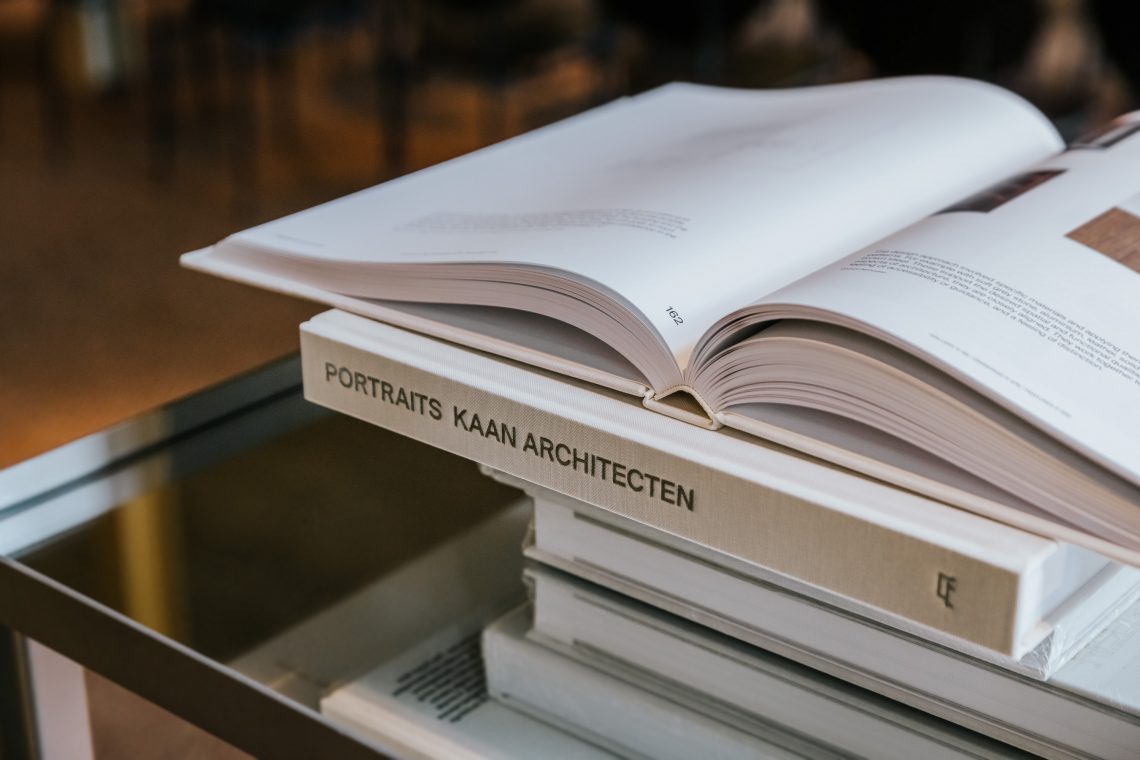

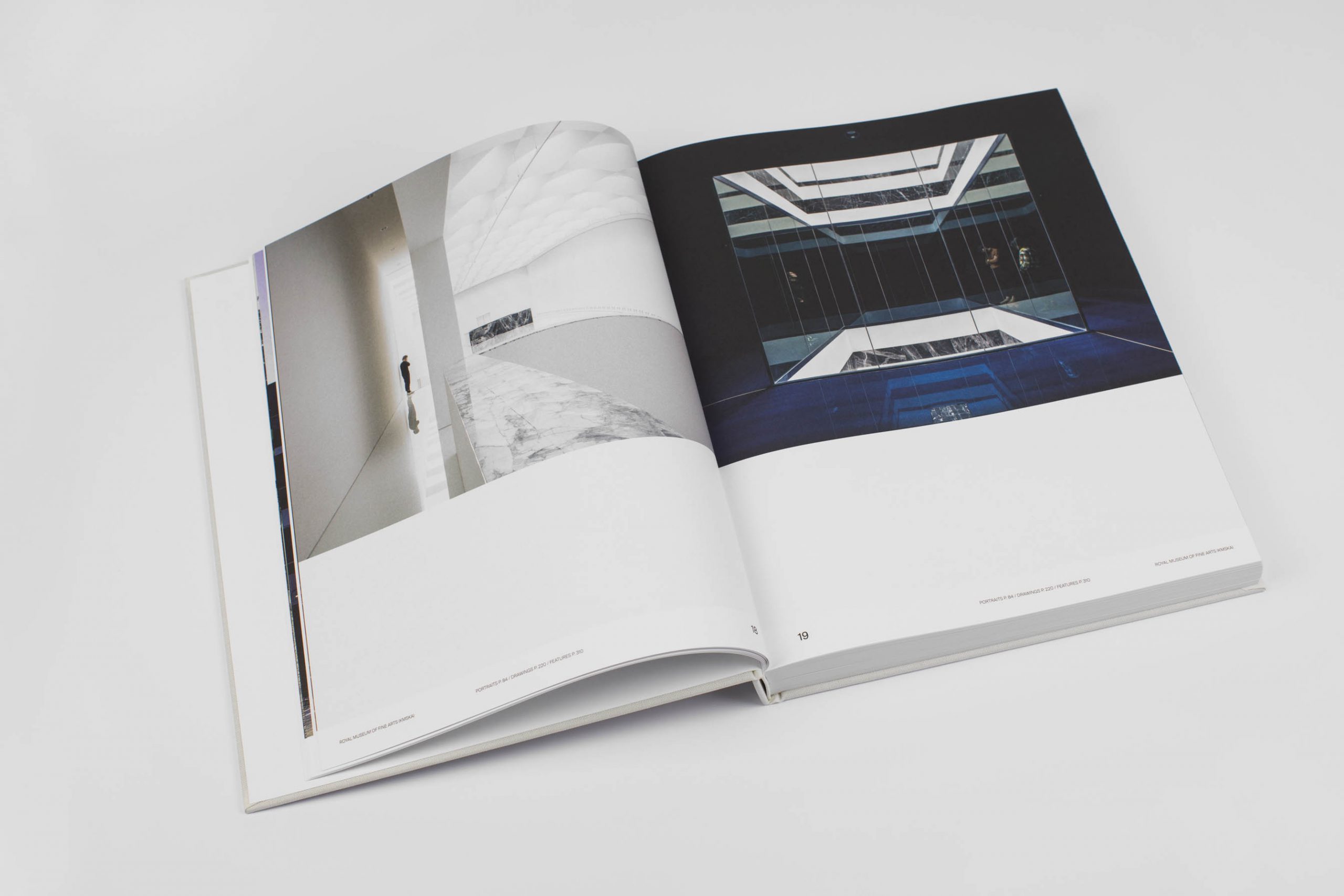

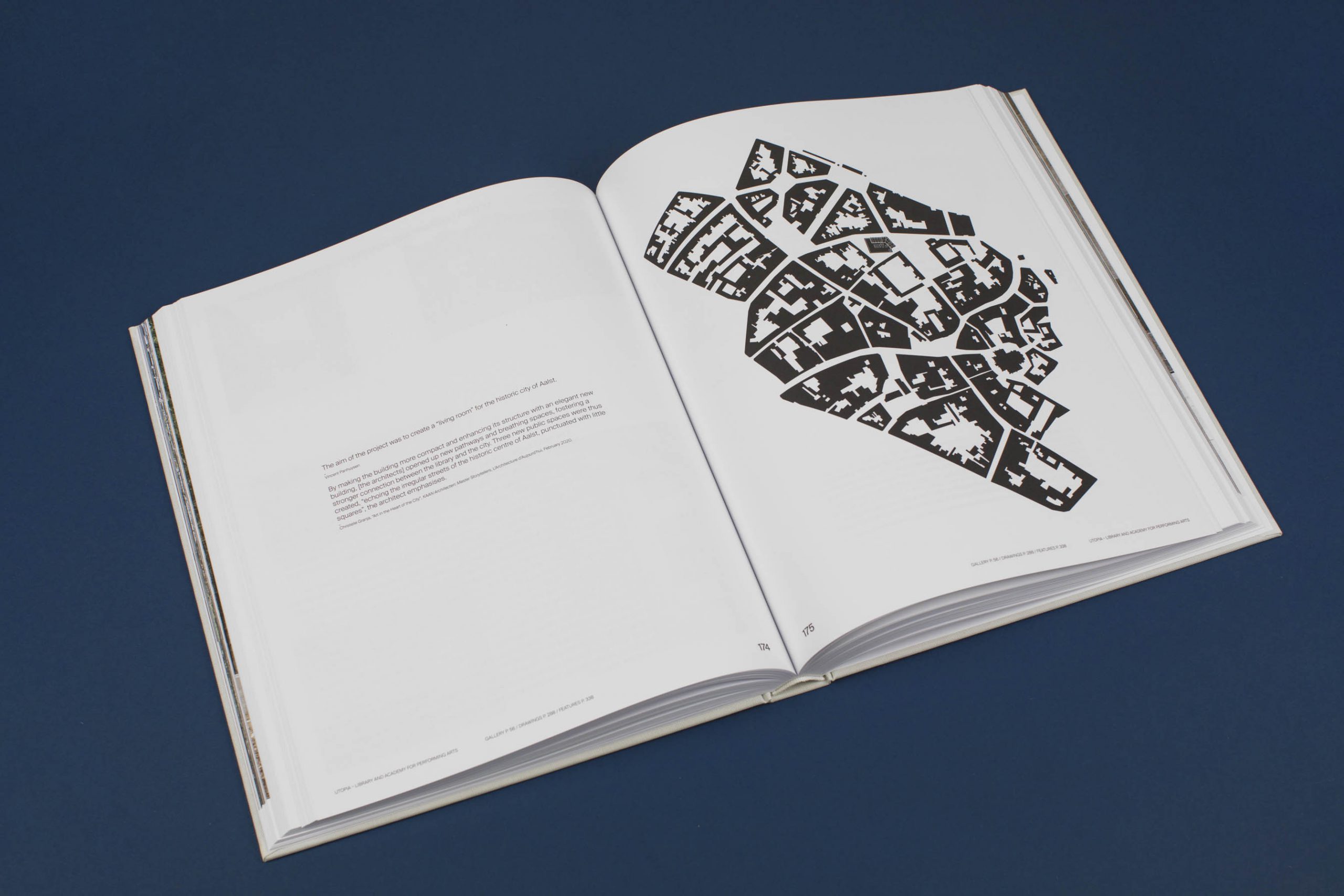

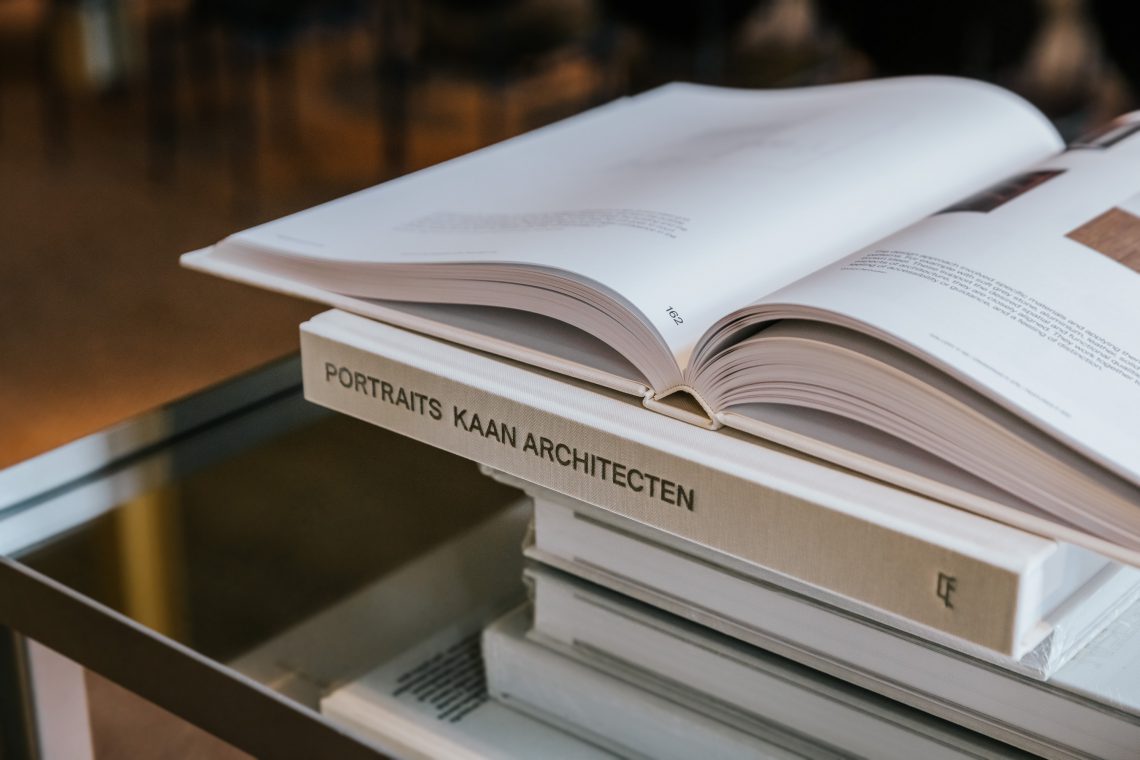

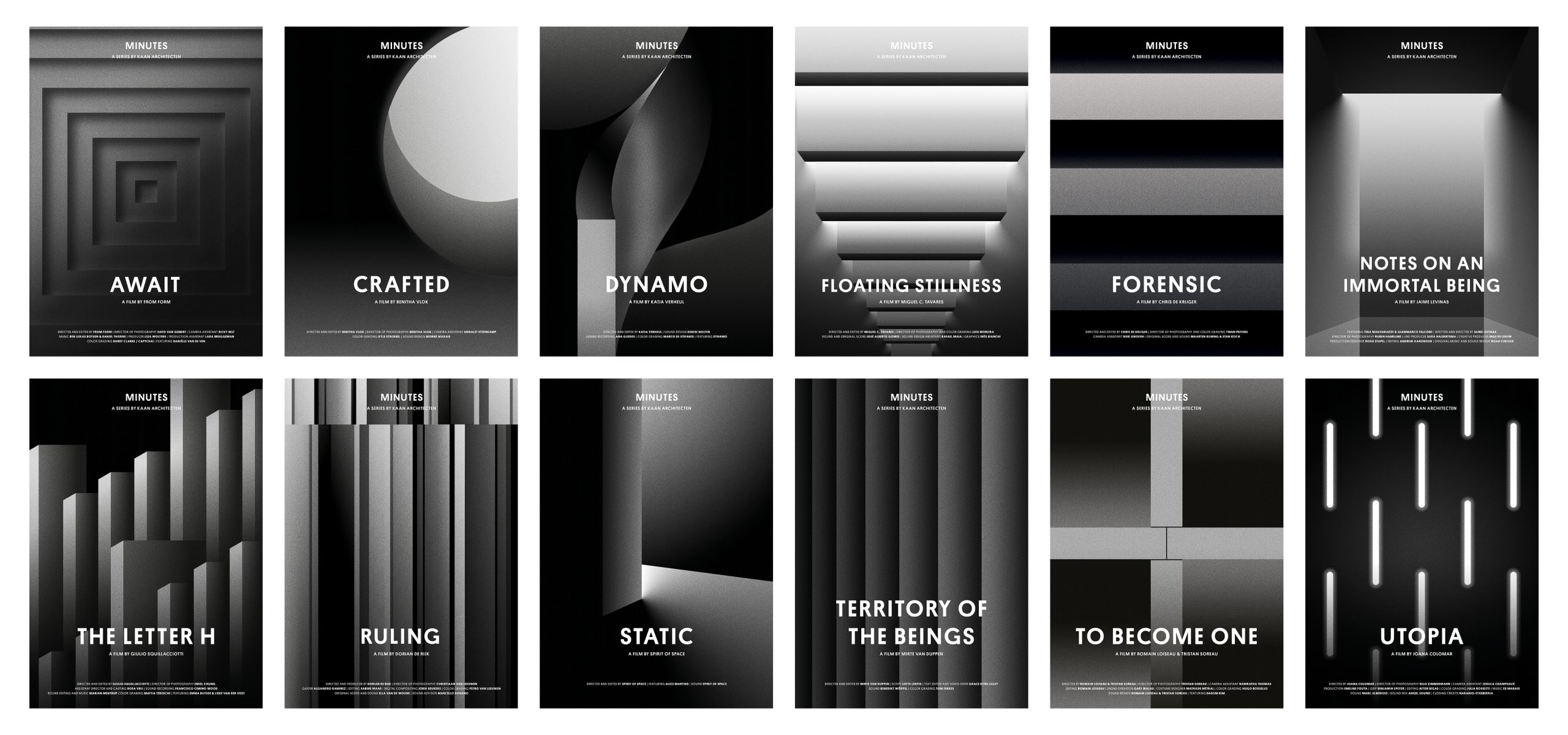

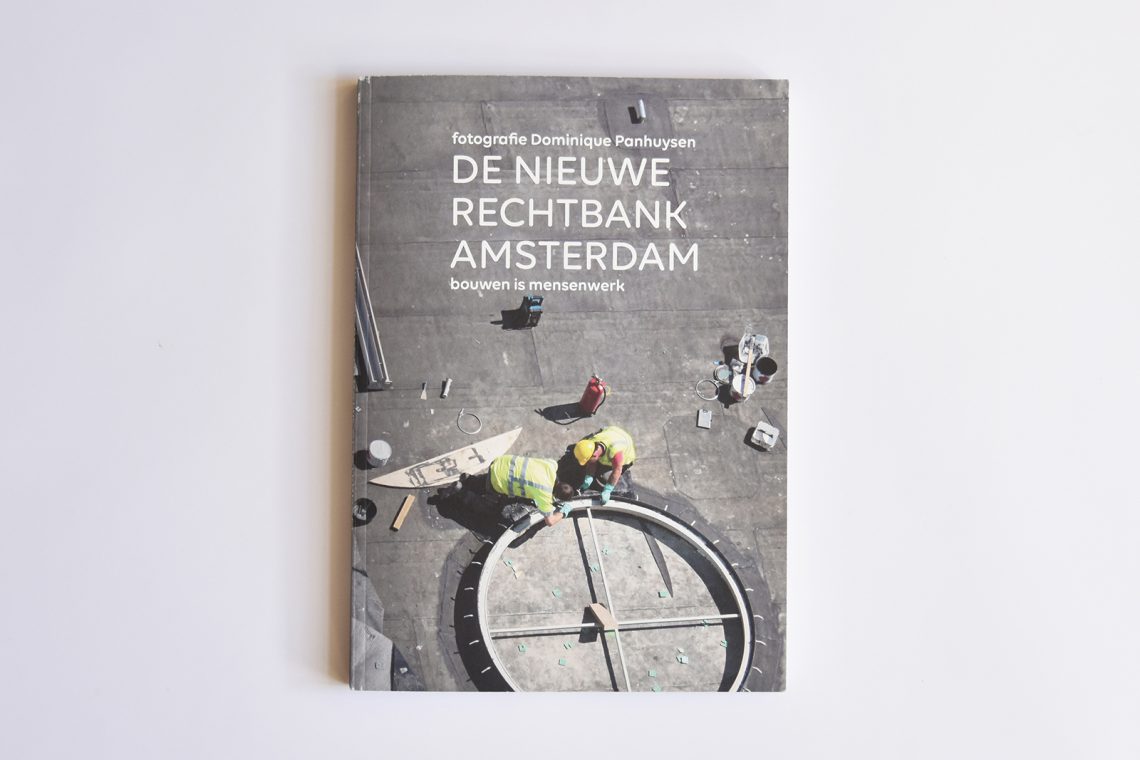

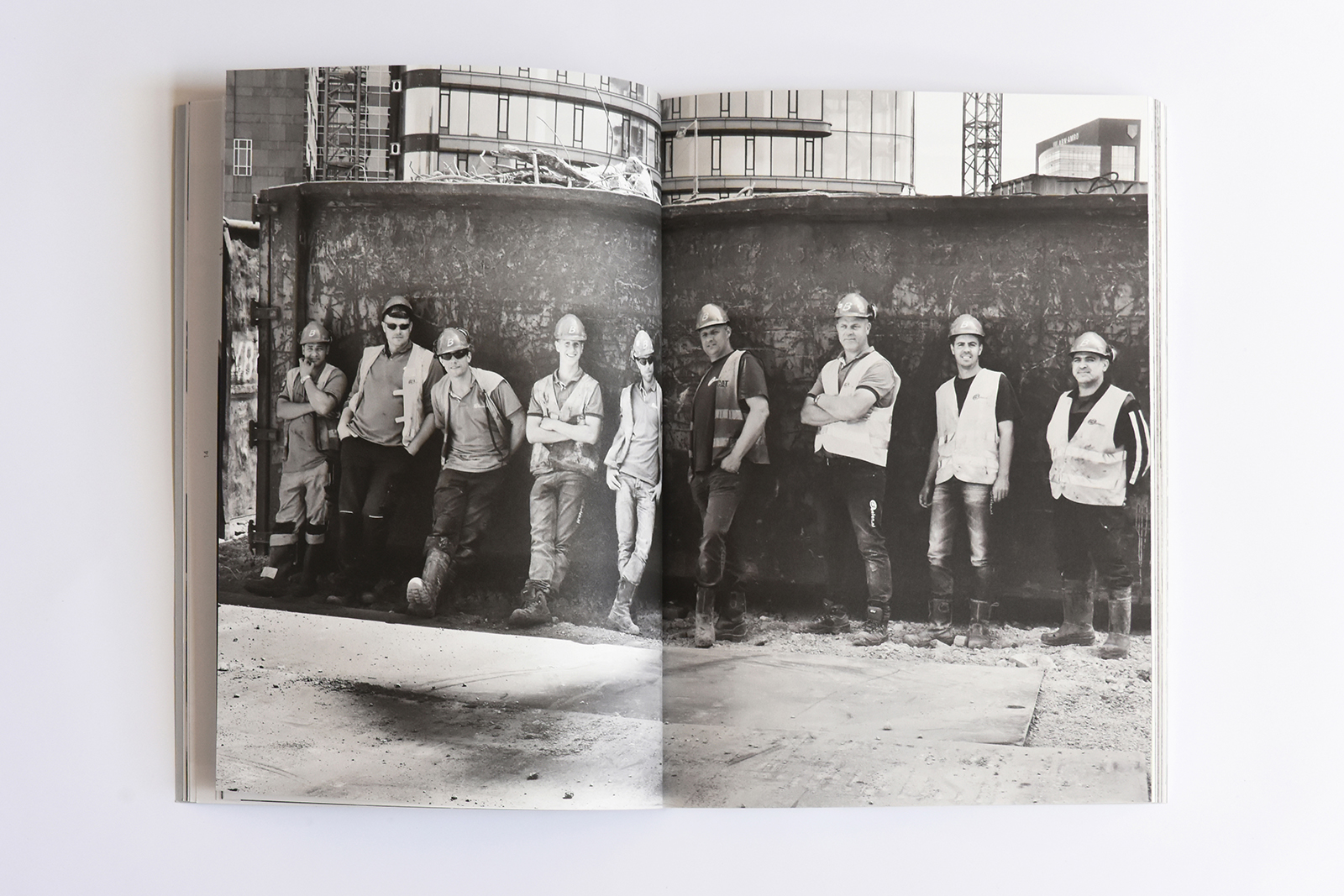

The book is a testimony to the efforts of everyone involved in the demanding building process, from engineers and architects to construction workers.

The book is a testimony to the efforts of everyone involved in the demanding building process, from engineers and architects to construction workers.

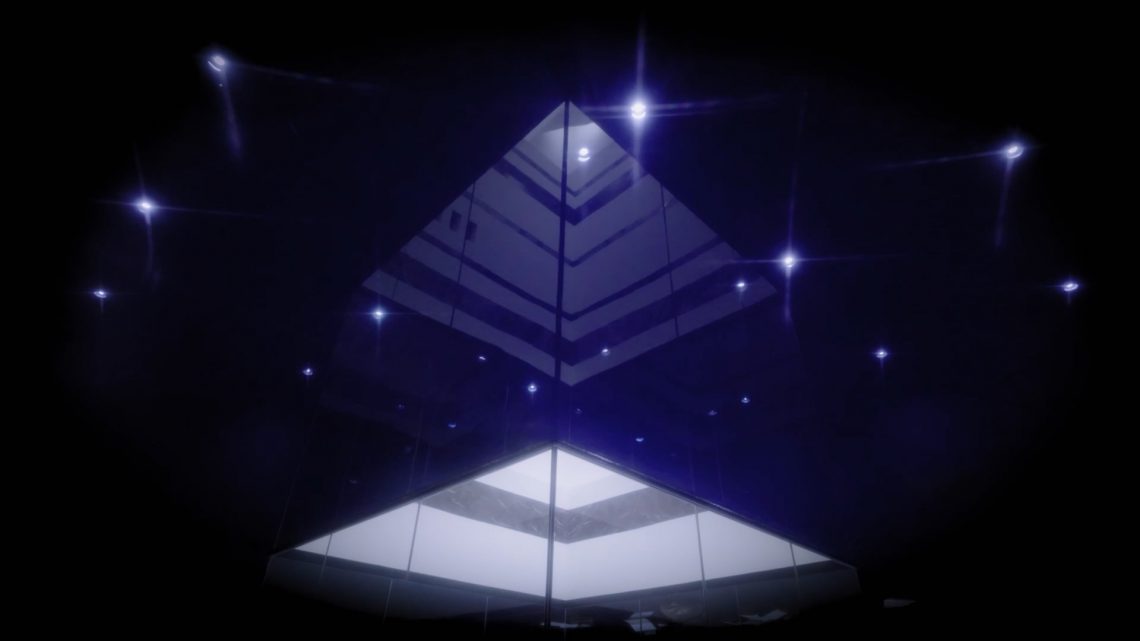

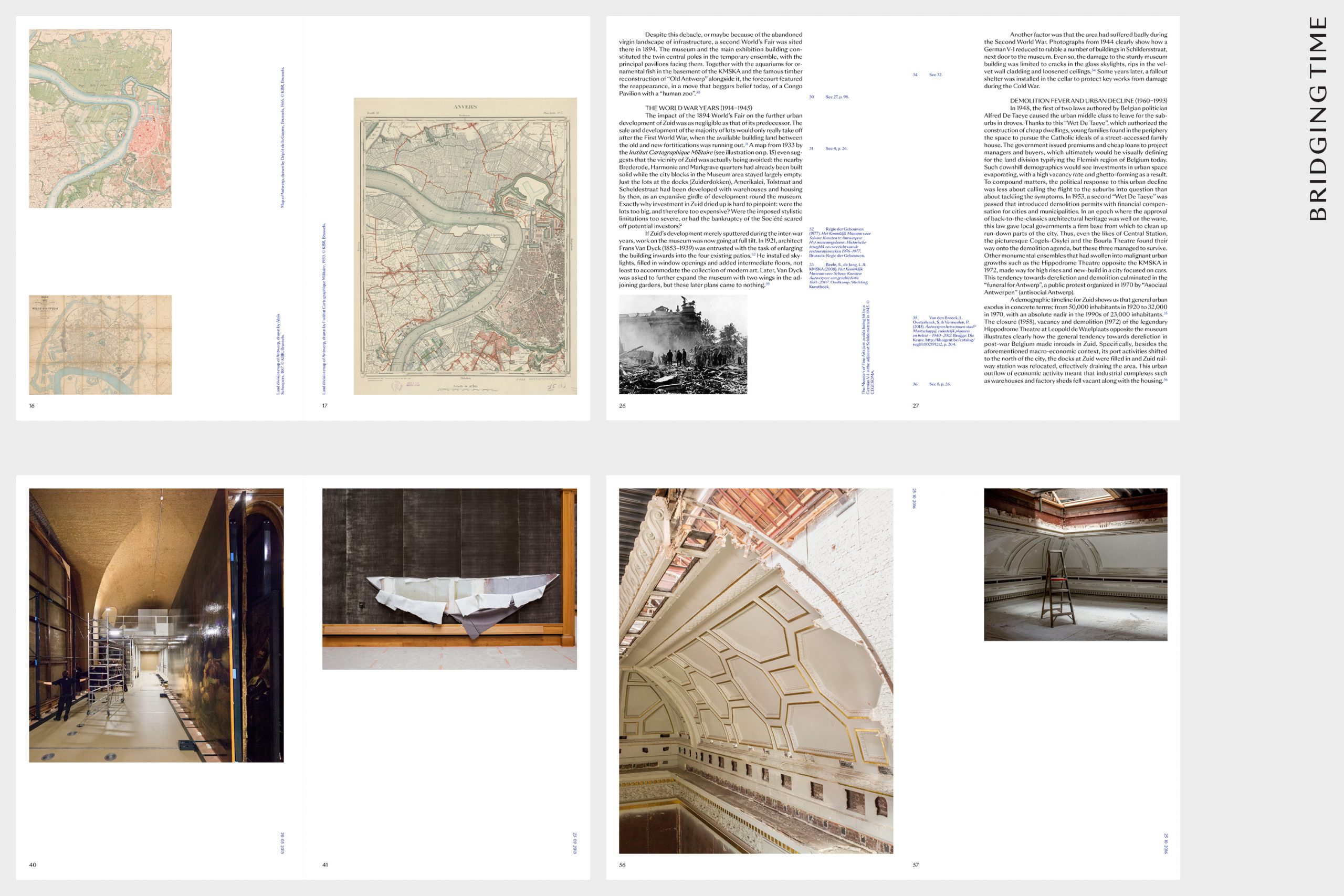

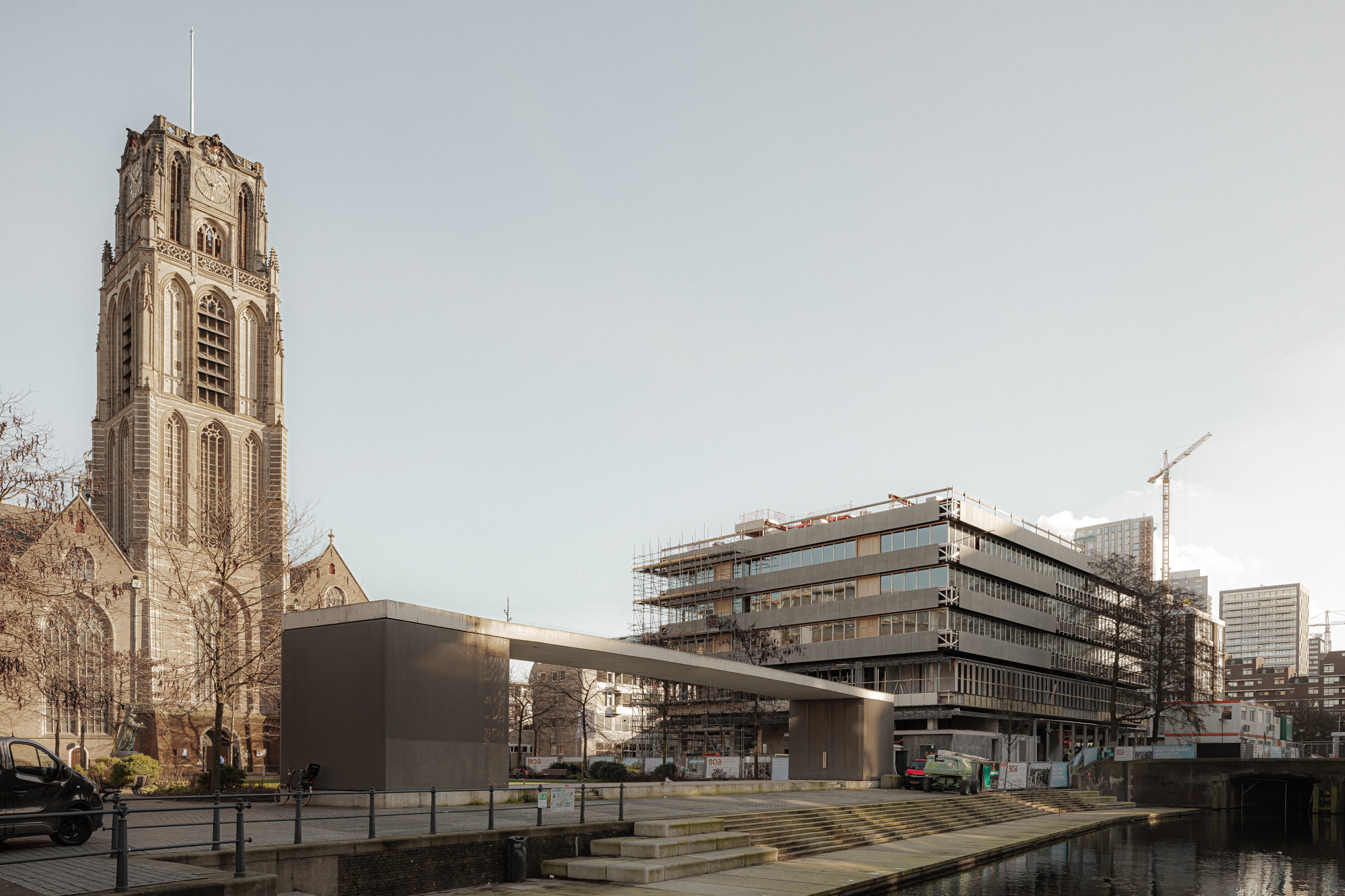

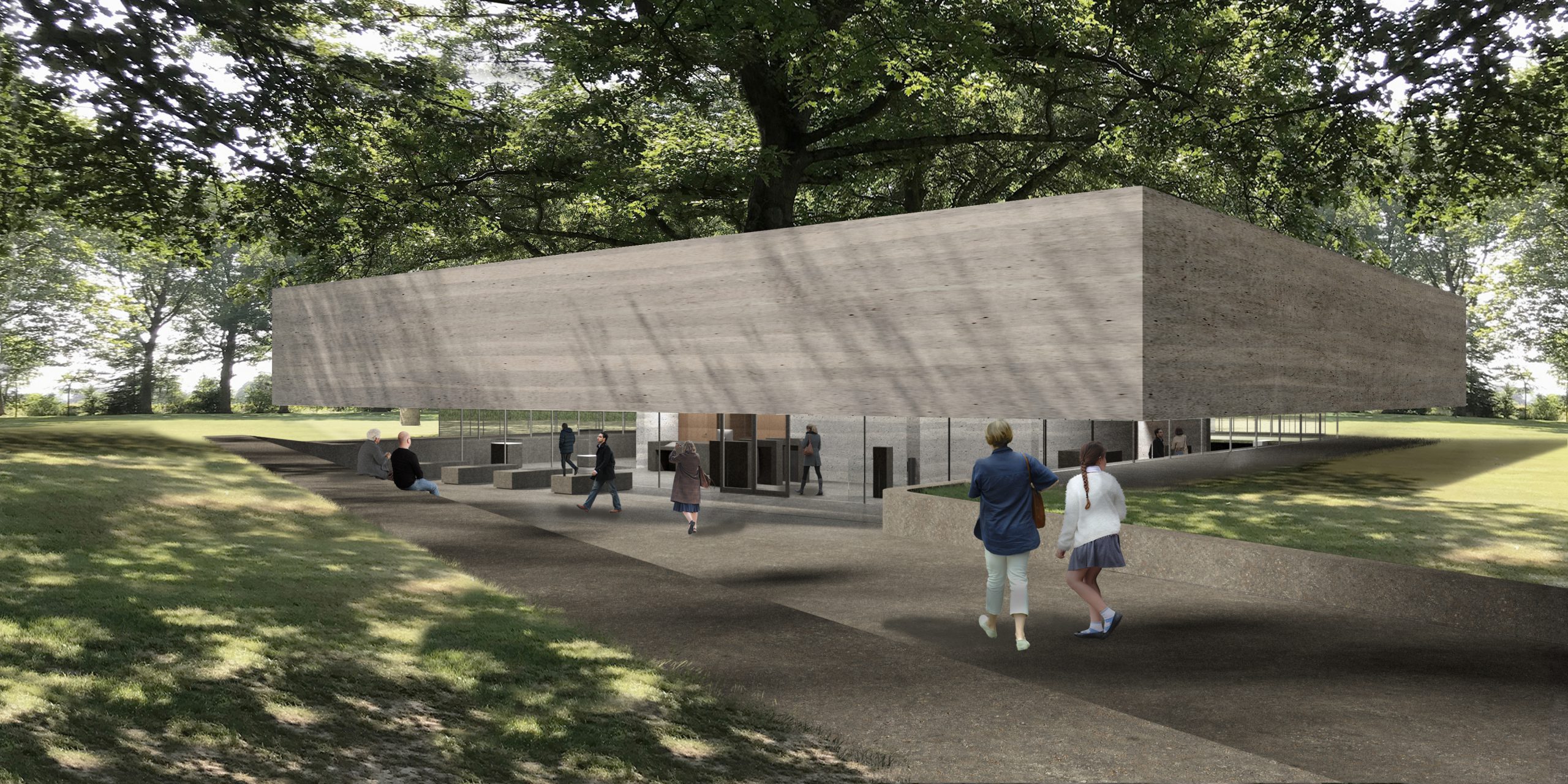

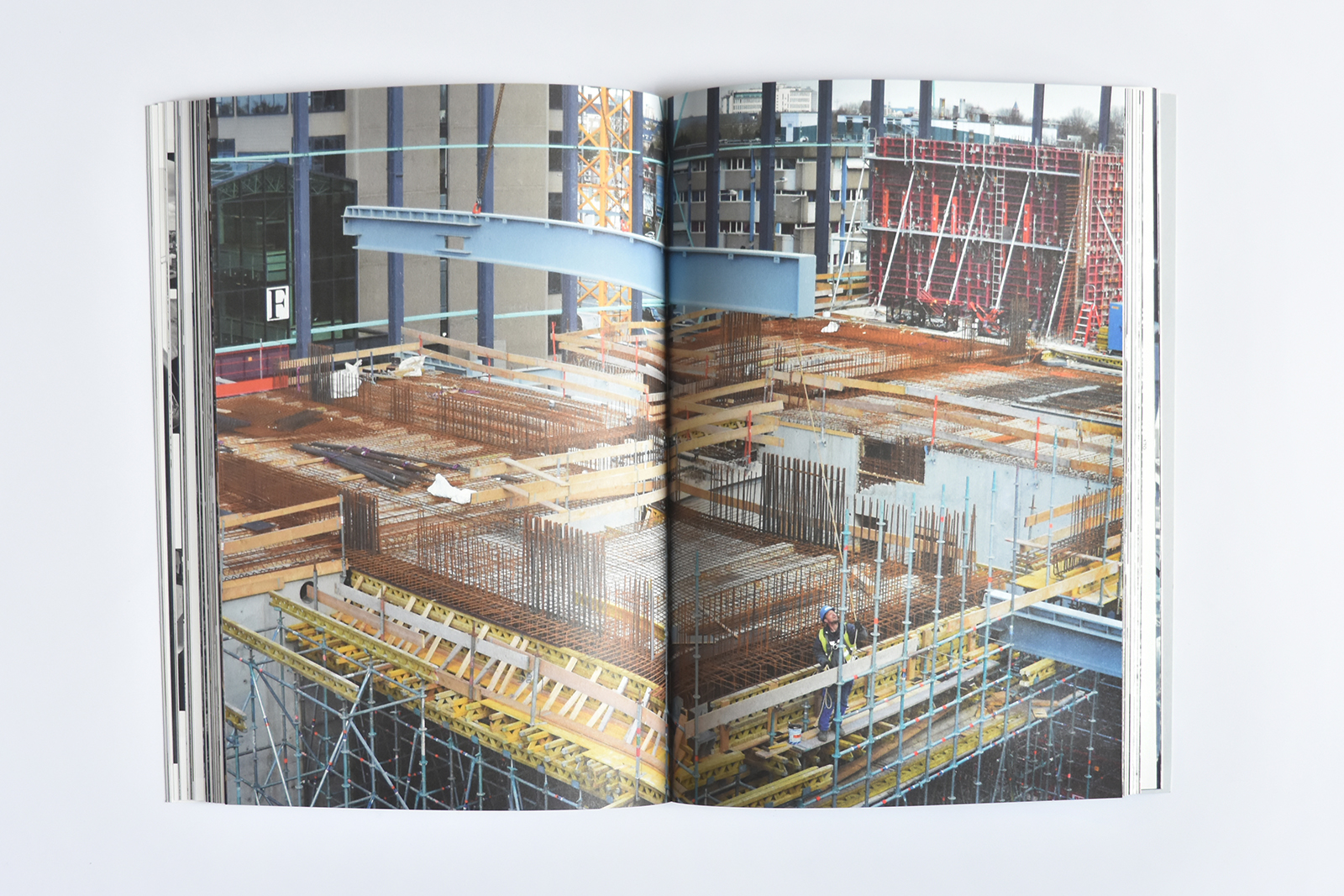

The openings in the roof are being executed while the structural work on the future exhibition halls is also in full swing.

The openings in the roof are being executed while the structural work on the future exhibition halls is also in full swing.

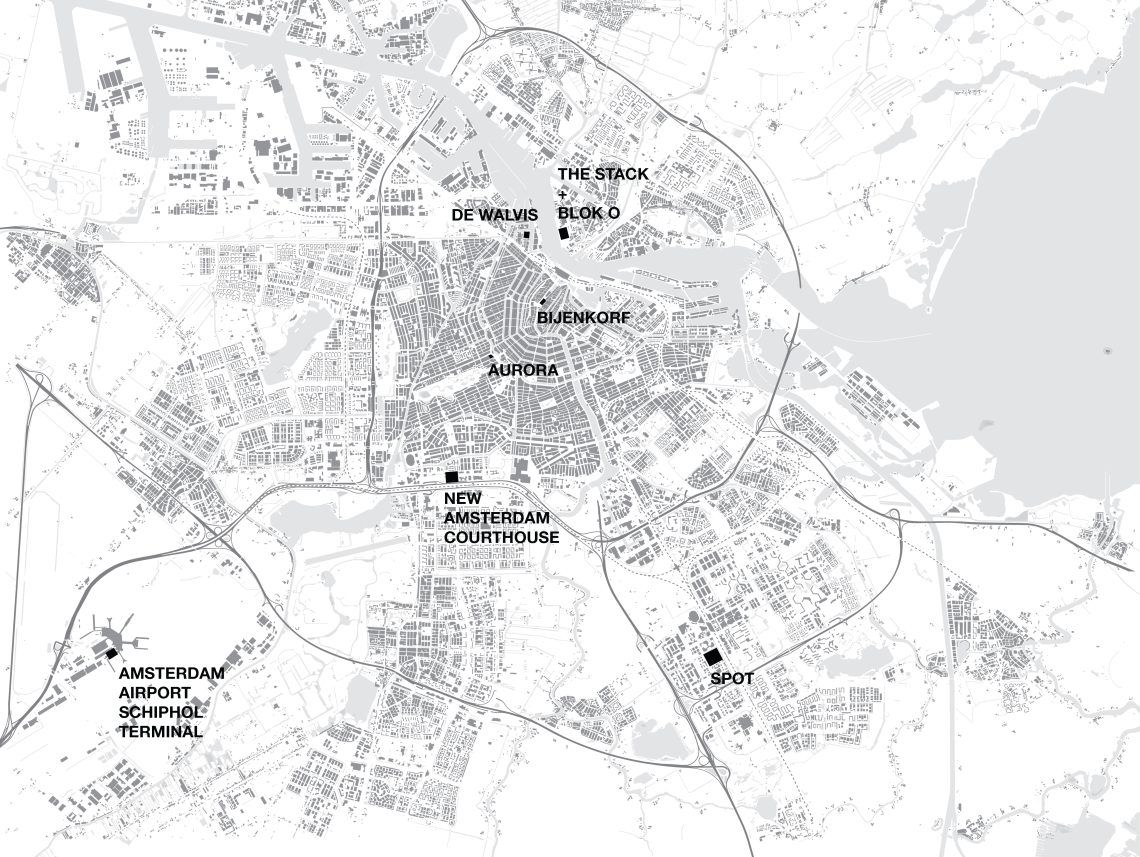

Keep an eye on

Keep an eye on